Kangxi Famille Verte Porcelain Baluster Jar

This lidded baluster jar was received from Kiplin Hall for conservation in June 2022. It was likely manufactured in China during the Kangxi period (1662-1722) and exported to Britain for its aesthetic value and as a status symbol. Conservation was undertaken to allow its display following the failure of its previous repair.

What was the goal the project set out to achieve?

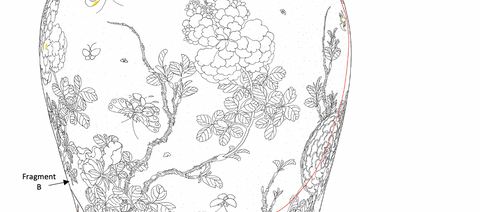

Prior to conservation the jar was in thirteen fragments. It had been previously broken and repaired with a proteinaceous adhesive which had embrittled, discoloured and failed through aging. The two largest fragments were still adhered together, though the join was significantly misaligned and there were concerns over its stability. Large amounts of adhesive residue and surface dirt were also present on the fragments and there were significant areas of loss surrounding the neck fragment’s break edges.

The primary aims of the project were therefore to remove the failing adhesive joins, clean the adhesive residue and surface dirt, re-adhere the fragments together and fill the areas of loss. Kiplin Hall also requested the adhesive label on the vase be removed prior to conservation and reapplied following treatment as it possessed historic value.

What did I do?

The adhesive label was removed via localized controlled humidification and cleaned using polyurethane make up sponges. FTIR and Teas testing were then used to determine the historic adhesive used on the jar. It was found to be a proteinaceous adhesive, so soluble in water. The ceramic fragments were therefore soaked in water for four days to help soften the adhesive residues and dismantle the fragments still adhered together. The softened residues were mechanically removed using a scalpel.

The fragments were then cleaned to remove surface dirt and remaining residues using cotton swabs impregnated with a 50:50 solution of ethanol and deionised water, with a few drops of a 10% Synperonic A7 in deionised water solution. They were then rinsed using cotton swabs impregnated with pure ethanol to remove surfactant residues. Following cleaning the staining of the break edges was reduced via three applications 2:1w/v solution of Biotex in 40C deionised water, applied as a paste.

The two large fragments were adhered using 40% Paraloid B72 in toluene (to allow greater working time) and the smaller fragments were adhered using 40% Paraloid B72 in acetone. The break edges were then painted with a barrier layer of 40% Paraloid B72 in acetone to aid reversibility of the fills. Milliput was used to fill the larger areas of loss and Pollycell Fine Surface Pollyfilla was used to fill the smaller areas and line cracks. The fills were sanded to shape using sand paper and micromesh cloths of increasing fineness. The fills were then colourmatched using acrylic paints to the off-white background of the ceramic and coated in a layer of Porcelain Restoration Glaze. The paper label was then adhered back onto the ceramic using 7.5% isinglass in deionised water.

What was the outcome?

The jar was successfully deconstructed, cleaned and reconstructed using a reversible, minimally interventive approach which was in line with the desires of Kiplin Hall. The surface dirt and aged, failing adhesive were removed, improving its aesthetic value and suitability for display, and reducing the risk of further damage via adhesive failure. Its historic and aesthetic value were also maintained by adding visually discernible, but minimally visually distracting, fills and retaining the adhesive label.

What did I learn?

This treatment allowed me to put into practice the theory of ceramics conservation that I had learned earlier in the year. I really enjoyed the challenge of conserving such a large ceramic object and the analysis needed to identify the unknown historic adhesive.