The Organic Conservation studio at the British Museum treats artefacts that have organic chemistry as their foundation, some of which are sensitive to treatments involving water and other polar solvents. For this reason, the studio has traditionally made use of non-polar solvents such as white spirit, xylene and toluene for cleaning, as wetting agents, and as carriers for consolidants and adhesives. However, these solvents are classified as a significant health and safety risk1; toluene for example is a carcinogen and affects the unborn child2. COSHH legislation requires that, wherever possible, these chemicals should be replaced by ones that are less hazardous. There is therefore a need for alternative solvents that are less hazardous to health than those in common use, specifically xylene and white spirit. In addition, any new solvent should not adversely affect the aesthetics or integrity of organic materials, and dissolve at least some of the more common conservation adhesives. These alternatives should ideally also be easy to obtain and less hazardous for the environment.

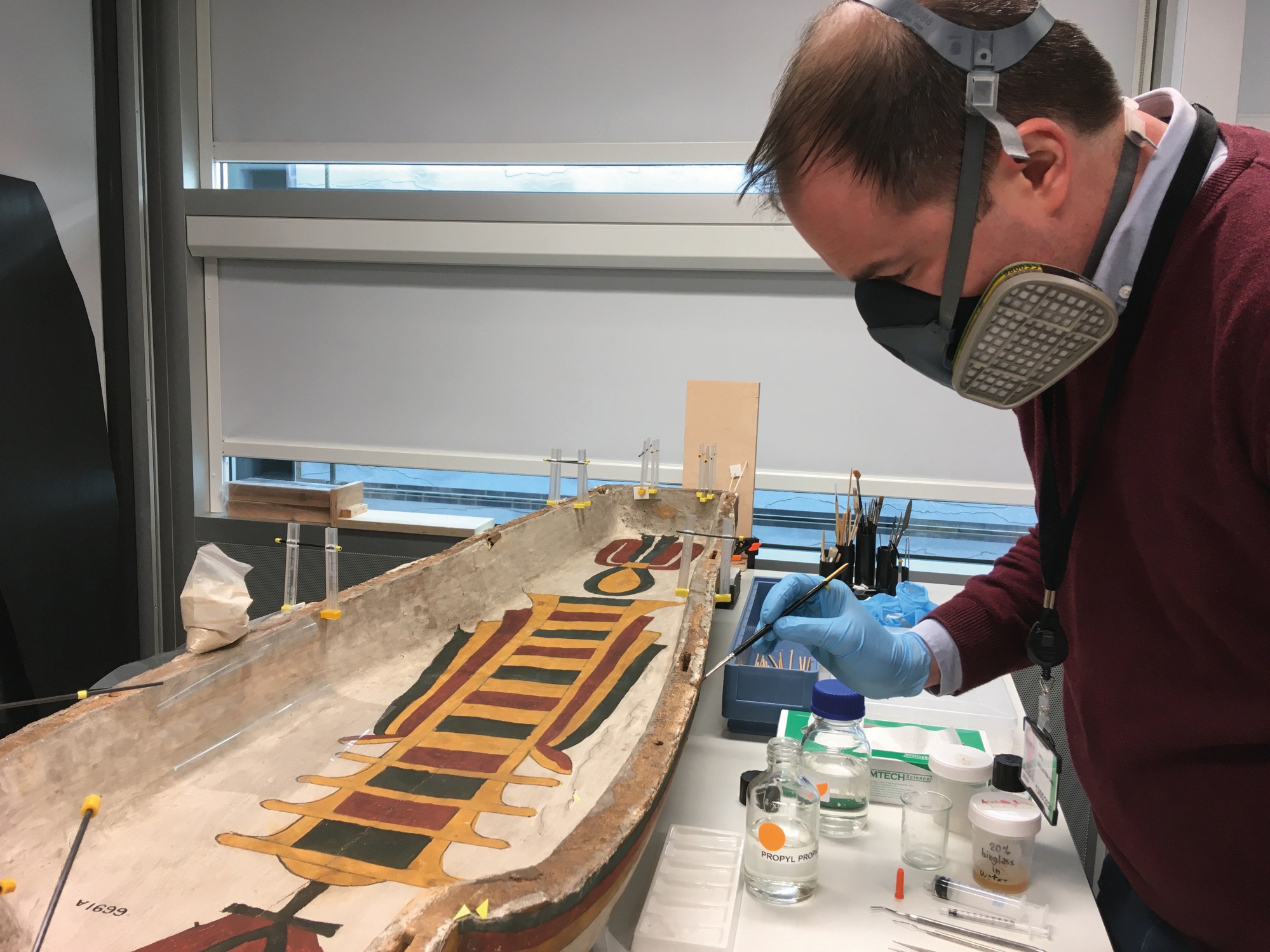

Propyl propionate was identified as one possible alternative through personal correspondence with Dr Paolo Cremonesi following his talk at the IAP/Tate ‘Gels in Conservation’ conference held in London in 2017. Qualitative, bench-side testing is currently being carried out in the Organic Conservation studio in order to better understand propyl propionate and its properties. This article summarizes the observations gathered by the authors relating to its use as a solvent for cleaning, as a wetting agent, and as a solvent for adhesives.

Material overview

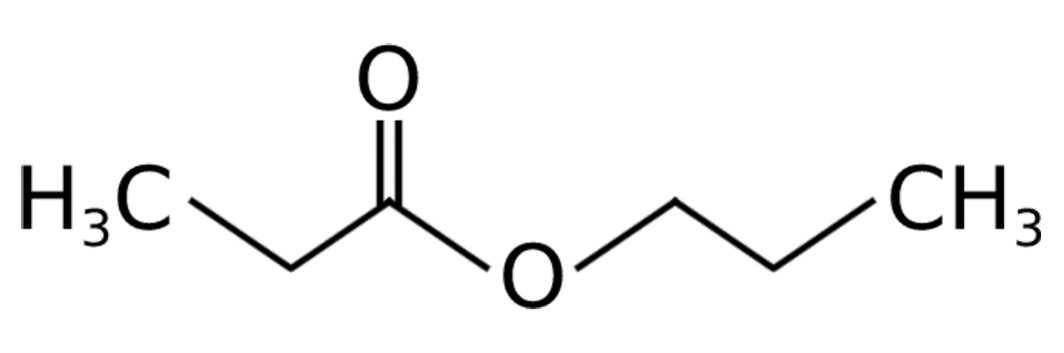

Propyl propionate is a colourless liquid with a pungent, ‘fruity’ odour. According to the H-phrases in its material safety data sheet3, propyl propionate poses a health risk similar to acetone, and less than that of IMS. It should be noted that as propyl propionate is a novel solvent in conservation, we continue to employ additional health and safety controls around its use. It is ‘a propanoate ester’ resulting from the formal condensation of the hydroxy group of propanol with the carboxy group of propanoic acid’4. It has the molecular formula C6H12O2. Figure 1 shows its structural formula.

Propyl propionate is of interest to bench conservators owing to its combination of a highly polar ketone group, as well as a less polar alkyl chain. Its Hansen solubility parameters are widely available5. It has a reported vapour pressure of 1.733 hPa at 20°C6, an evaporation rate only slightly faster than xylene – and an order of magnitude less volatile than ethyl alcohol (IMS/IDA), let alone acetone7. However, anecdotally we have found it evaporates relatively quickly - somewhere nearer to IMS both when used as a wetting agent and as the solvent carrier in adhesive/consolidant mixtures.

Use on the bench

Practical testing has so far focused on the effectiveness of propyl propionate in three areas of application: as a solvent for cleaning purposes, as a wetting agent, and as a solvent for adhesives.

First, let’s look at the use of propyl propionate as a solvent for surface cleaning. Propyl propionate was tested as an alternative to white spirit and xylene for wet cleaning light-damaged East Asian lacquer surfaces, which are sensitive to polar solvents. The cleaning process involves introducing a drop of solvent (<1 ml) onto either a piece of soft cotton cloth or a lab-grade soft paper tissue and lightly cleaning a small 5-10 cm square of surface at a time.

Propyl propionate tended to evaporate faster than xylene when used in this way. Propyl propionate also seemed to produce slightly less friction between the cloth and the surface than xylene or white spirit. This proved useful in instances were only a light clean was required but made the removal of more stubborn accretions harder as there was less ‘bite’. Despite relatively extensive use as a cleaning agent for East Asian lacquer surfaces, no negative impacts on the lacquer coatings have been noted macroscopically, such as the development of whitish hazing, staining or tide marks, including for artefacts subsequently on display for over 12 months.

Secondly, we can discuss propyl propionate’s efficacy in pre-wetting water sensitive surfaces to facilitate the use of water-based adhesives. This technique involves saturating the area to be treated with non-polar solvent to prevent staining of the surface, and is used for example, when seeking to resecure a surface coating with an underbound pigment to its substrate using an acrylic dispersion or emulsion. In this context, pre-wetting serves to confine the subsequently introduced water-based adhesive to the space in between the solvent saturated surface layer and substrate, therefore avoiding excessive migration of either adhesive or its carrier solvent (water) into the water-sensitive surface of the artefact. White spirit has traditionally been used for this purpose.

Volumes of propyl propionate between 1 and 10ml were used to wet out areas up to 100 x 50 mm of the decorative surface of a range of artefact types. This was immediately followed by the application of up to 5 ml of adhesive, including 80% Primal B60A (an aqueous acrylic emulsion) and Lascaux Medium for Consolidation 4176 (an aqueous dispersion of an acrylic copolymer).

The relatively fast evaporation rate of propyl propionate compared with white spirit reduced the working time available. However, propyl propionate has shown no tendency to leave stains or tidemarks once evaporated and following successful use on four late-period Egyptian coffins, a painted 6th century Chinese Buddhist panel, and two 14th century Japanese Buddhist sculptures, it is now in routine use in the studio as a pre-wetting agent.

Thirdly, we can assess propyl propionate as a carrier solvent for adhesives. Paraloid B72 (copolymer of ethyl methacrylate and methyl acrylate) dissolved in xylene is often used in situations where a polar solvent might have an adverse impact on the artefact to be treated.

It was found that propyl propionate readily dissolves concentrations of Paraloid B72 between 3 and 20% w/v. Solutions of Paraloid B72 in propyl propionate were used as an adhesive on wooden artefacts for structural work, and on artefacts coated with Asian lacquer to secure lifting/tenting areas of decorative surface.

Wooden artefacts treated with solutions of Paraloid B72 in propyl propionate required 24 hours' curing time. The same adhesive system introduced to secure lacquer flakes only required 72 hours to cure – a slight improvement on the 96-120 hours curing time recommended for Paraloid B72 in xylene. The rheology of propyl propionate/Paraloid B72 solutions seems to suggest a relatively low surface tension, more akin to B72 systems in acetone than in xylene. It should also be noted that propyl propionate appears to slightly swell the rubber stopper in syringes, making delicate application via this method challenging.

Further tests show that propyl propionate also dissolves acrylic resins Paraloid B67 and B48, as well as Mowilith 30 and 50. It is not an effective solvent for cellulose derivatives such as Klucel G (hydroxypropyl cellulose) or for natural resins such as unbleached shellac because it is a non-hydrogen bond donating polar solvent, and both Klucel and shellac have solubility parameters dominated by hydrogen bonding. All materials were tested at 5% w/v solids/solvent, but Paraloid B72 has been successfully dissolved at a far wider range of concentrations as detailed above.

Conclusions

In many cases Propyl Propionate appears to be a highly effective replacement for non-polar solvents in cleaning, pre-wetting, and adhesive treatments on water-sensitive surfaces, and a promising candidate for further testing. Next steps could include research into its efficacy as an adhesive carrier, and its rate and extent of evaporation, including the presence of any residues on artefacts.

Author biographies

Verena Kotonski ACR

Alex Owen

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Paolo Cremonesi (independent conservation scientist, Lodi, Italy), who first drew our attention to propyl propionate as a possible alternative to xylene.

Supplier

Propyl Propionate (99%)

Sigma Aldrich

www.sigmaaldrich.com

Merck Life Science UK Limited

The Old Brickyard

New Road

Gillingham, Dorset

SP8 4XT

United Kingdom