The Prittlewell Anglo-Saxon chamber grave was uncovered in Essex in 2003 by MOLA (Museum of London Archaeology) during a routine road-widening project, providing a remarkable glimpse into early Anglo-Saxon burial practices. Liz Barham recounts the meticulous conservation and scientific analysis that followed, highlighting the challenges faced by the multi-disciplinary team as they worked to preserve and interpret the findings.

Introduction

The discovery of a princely Anglo-Saxon chamber grave in Prittlewell, Essex by MOLA (Museum of London Archaeology) in October 2003 was an astounding and unexpected find. Discovered beneath an ordinary strip of grass verge during an archaeological evaluation prior to a road-widening scheme, it was nationally and internationally significant, as well as very special for local people.

The widely collaborative analysis project that followed gathered together around forty specialists, including some fifteen scientists, and in the course of events it took in documentary and press coverage, temporary displays in Southend, London, Sutton Hoo and Paderborn, Germany, academic seminars and numerous lectures and talks by the core project team. It is now complete with an academic volume (MOLA 2019), a book aimed at a non-specialist audience, the objects returned to Southend and a selection on permanent display.

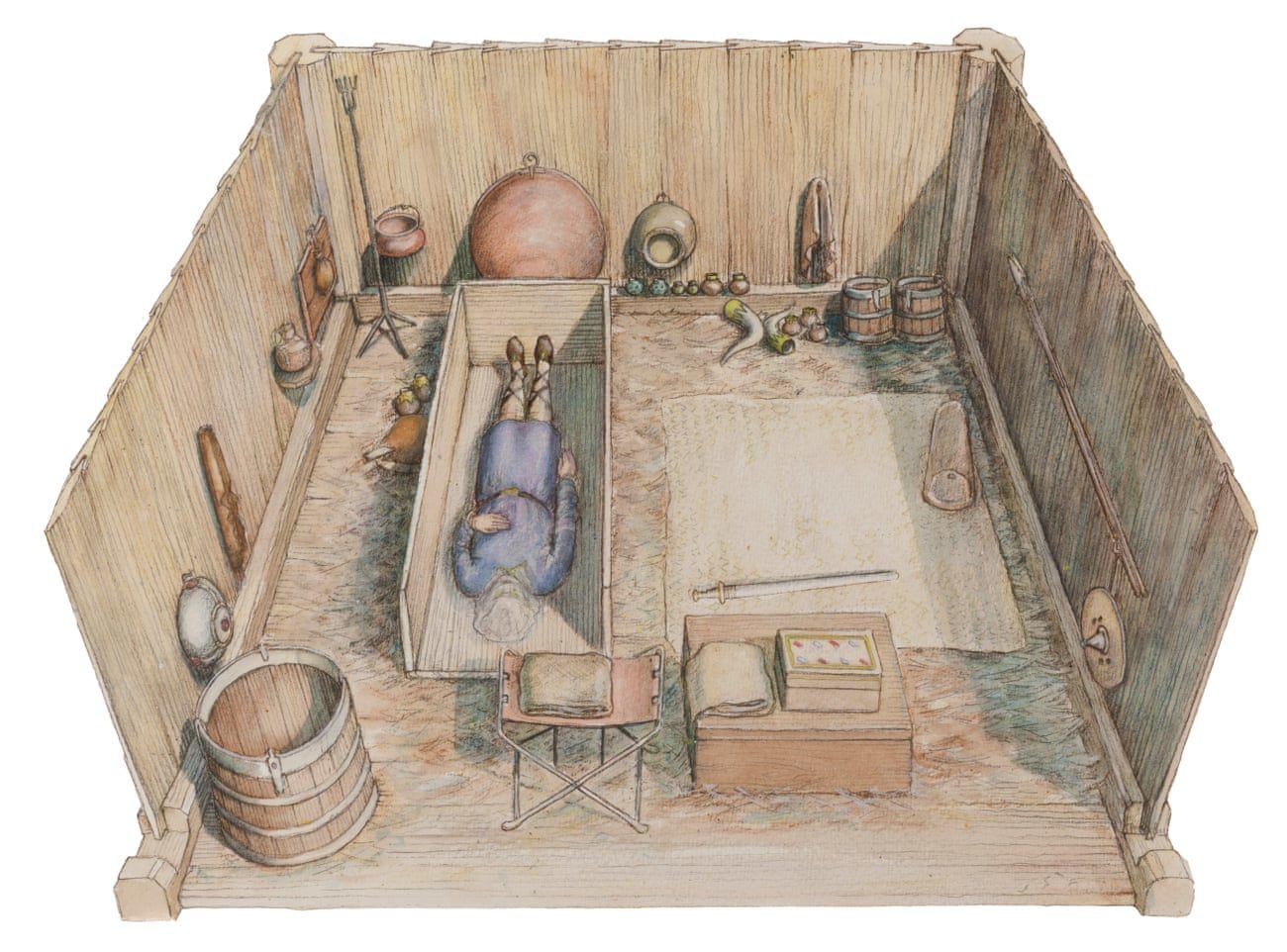

The burial consisted originally of a large wooden chamber beneath a mound and within it, a man placed in a coffin, surrounded on the walls and floor by buckets, cauldrons, bowls and drinking vessels, a lyre, a sword, a folding stool, a scythe, and lighting equipment. There were gold foil crosses, probably placed over his eyes, and gold coins, possibly placed in his hands, and buckles on his clothing. This was a rare opportunity to use modern archaeological and scientific techniques to examine, record and analyse such a burial. These were particularly valuable as the organic remains were generally poorly preserved except as mineral preserved fragments around heavily corroded metal fittings and surfaces, some of them surviving only as stains in the ground. The body itself was no longer present, except for tiny fragments of tooth enamel.

The circumstances of the discovery and conservation experiences during and just after the fieldwork stage of the project were reported soon after that work began. Here we report on some of the challenges and surprise results of the work at the analysis stage and note the value of archaeological conservation for its intimate perspective on the finds, from early work on-site, throughout the forensic investigative process and in drawing together scientific analyses to inform the rest of the project.

The Early Stages

The project was undertaken according to the staged approach defined in Management of Archaeological Projects 2 (MAP2: English Heritage 1991) and its successor Management of Research Projects in the Historic Environment (MoRPHE: English Heritage 2009). Following on-site recording, most of the objects from the chamber grave were lifted in soil blocks for recording and micro-excavation in the laboratory. The initial investigation of these blocks was undertaken soon after lifting to ensure that they were examined before deterioration of any ephemeral remains, to stabilise more fragile elements and to clarify surfaces through X-ray and investigative cleaning. It was also to facilitate the assessment of potential that the project team would be required to undertake prior to the analysis phase of the project, comprising in-depth investigative conservation and scientific analysis to support finds specialist reports, illustration and photography for the site publication.

The updated illustration of the reconstructed burial using precise results from the analysis project.

A Multi-Disciplinary Team

In fact, analysis work was delayed by political decisions about the road scheme which had a knock-on effect for assessment and funding, so further work could not get underway until 2012. It was fortuitous that the conservators who had lifted and worked on the finds at fieldwork remained in post throughout all phases of the project, providing a valuable continuity of knowledge of the finds and their contexts on site.

MOLA appointed team leaders to bring together the specialist work and as such the lead conservator was central to the coordination of the conservation work at MOLA and the scientific analyses undertaken by external institutions. This was beneficial so that sampling and analysis took place in conjunction with the investigative conservation programme, within an intensive schedule requiring completion within approximately fifteen months.

The most integrated group of specialists were those examining mineral preserved organics: animal derived remains, wood and plant-fibre, and textile. When there were composite objects these specialists sometimes came in to work together, contributing to annotation of the same diagrams, which assisted the interpretation of degraded surfaces and their relationships.

For example, the work on the sword from the chamber floor was very much a joint enterprise between specialisms: within the corrosion of the blade lay traces of an ash wood scabbard lined with sheep wool, possibly covered by skin or leather with a tape-and-cord binding at the scabbard mouth, a horn hilt and textiles probably laid over the upper surface. X-ray had already shown that the sword was pattern-welded with a displaced iron angle bracket from the coffin corroded to it; this was covered in textile from the surface of the coffin.

Where possible, external specialists came to examine objects in the conservation laboratory rather than objects going out to individuals. This was partly due to the large size and fragility of some objects and for time efficiency, but it also enabled them to make observations and discuss them as the conservation work progressed.

View of the burial chamber being excavated with emerging array of grave goods.

Conservation Approach and Findings

From the start, the conservation work on this burial was not just about preserving objects but studying them in detail and collaboratively with other specialists. This was essentially a continuation of the work on-site, in which subtle details such as wood stains from the chamber structure had been skilfully planned in by the archaeological team. Together we investigated their surfaces in soil and corrosion, their layering and constituent parts, looking for fine details such as evidence of decayed elements, wear and repair and examining their orientations and the remains of materials attached to them from their burial context.

It was possible, for example, to see wear from usage under the microscope on the rim-clips of some of the drinking vessel rims, perhaps through rubbing against a storage-box lid or even through resting upside down, maybe to dry them after use.

Wear on the delicate ridges of gilded lyre fittings on the flat front and back suggested that they had been slightly abraded over time, perhaps in drawing it in and out of a bag. Animal hairs (too degraded for full identification even under electron microscope) were found on the underside of some of the fragments, suggesting, along with the fact that the lyre lay face down, that it was originally placed in an animal-skin bag.

There were also traces of plant-fibres in these areas, helping to establish that there were random strewn grasses and possibly other plant stems on the chamber floor, as well as remains of what appeared to be woven (possibly rush) matting.

Sometimes it was important not to clean away soil but to leave it as the last evidence of an object or structure; the only surviving evidence of a tongue-and-groove joint from the chamber wall was a woody stain preserved in a lump of soil attached to one of the wall-hooks. Soil was also left in situ where it added to the completeness of some objects; a pair of buckets were no more than a series of iron bands supported in situ by the soil separating them. One of these buckets was consolidated as such and can now be displayed as found. It was agreed by the project team that the scythe embedded in the soil base of the largest bucket would not be removed for more detailed measurement to avoid destruction of the bucket as a fascinating whole object.

The full significance of some observations made while the objects were fresh from the ground was not always apparent at the time, but through X-ray or CT scanning, through images, drawings and notes made during the process, sometimes with an archaeological illustrator’s assistance, we could look back at these at later stages when new questions arose about objects, about the structure of the chamber and the taphonomy (fossilization process) of the burial.

Recording the relationship of the drinking vessels, some of which were lying on top of each other in soil blocks, through X-ray and photography, and relating that to their site orientation, provided key evidence about how the array of vessels had been placed originally and moved as a group over time, and therefore about the structure on or against which they were sitting and the potential length of the horns’ tips no longer present. The recording of approximately 20mm of soil between the lyre and a conglomerate of corroded iron spearheads that had fallen onto it from the wall as indicated by the wall-hook corroded to them, contributed to the evidence that the chamber was not originally filled in and had remained a void for some time after it was closed up and the mound built above it.

Treatment Issues and Findings

The conservation treatment of some objects was challenging. Four drinking bottles had decorative collars and mounts in gilded copper alloy and silver, attached to the remains of a maple-wood neck and upper part of the bottle. The wood was decayed and the mounts encrusted with bulky copper alloy and silver corrosion, pushing off flakes of the gilding. Immersion of the wood in polyethylene glycol (PEG) might have caused many of the corroded and flaking mounts to float away. A wax cradle was made with a separating tissue layer in order to invert the object and pipette on PEG solution over five months. Following that, these objects were frozen and effectively freeze-dried very slowly in the freezer to avoid stressing the fittings by placing the objects under vacuum in a freeze-drying chamber. After drying, the wax support could be removed, some of the more bulky metal corrosion pared down and the gilding reattached with a stable consolidant, sometimes with additional Japanese tissue supports.

Drinking bottle with conservation complete (Rim diam 59mm).

Painstaking cleaning under the microscope revealed some breath-taking surprises: a painted design in red, white and yellow was discovered on the underside of a fragment of woodthinly encrusted with a dark layer of plant-fibre and fungal remains. The collection of tiny samples of corrosion and corroded solder from the hanging bowl, under one of the decorative ribs removed for investigative cleaning, produced six tiny fragments of spiral-spun gold thread, so small as to hardly be visible to the naked eye: under SEM it was found to be approximately 0.2mm wide and 0.004mm thick. These fragments appear to have been caught on the decorative rib of the bowl, perhaps from the sleeve of the last person to handle it.

The scientific analyses added immeasurably to the finer understanding of the finds. Most notably perhaps, given the poor preservation of some of the bone, it was possible, using tiny samples through Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry, to identify the species of the bone of the gaming pieces (probably from the rib or ribs of a sperm whale). And a bone placed with two of the drinking bottles next to the coffin appears to have been a joint of beef – the deceased’s share of the feast.

Even more importantly for the burial overall, it proved possible to date it to earlier than originally thought. This was done with the help of high precision radiocarbon dating using Accelerated Mass Spectrometry on very small, selected samples from a drinking horn and wood from a drinking cup, in combination with statistical modelling (taking into account data from the new national dating framework for Anglo-Saxon graves). The resulting date range for the burial was cal AD 575-605 (95% probability) with the starting date narrowed by evidence from the coins to 580 AD at the earliest. This makes it the earliest of the dated Anglo-Saxon princely burials and provides us with a new window on early Christian belief among the elite families of the East Saxon Kingdoms.

One of the two drinking horns: their fittings provided vital organic material for successful radio carbon dating. They gave date ranges for the death of the animal who's horns were used.

It was a great privilege to work on the remains of this burial, and those involved felt a great responsibility, because the discovery of an intact chamber grave of this nature is extremely rare and demonstrated its potential in the course of the work to offer some completely new insights into the elite Anglo-Saxon life and burial practice. This was reflected in the number of scientific specialists and institutions who, working with MOLA, generously gave their time and expertise to investigation and analysis of the finds. We anticipate that the results of the work will stimulate and contribute to academic research and popular debate in Anglo-Saxon archaeology for many years to come.