The wedding dress of Princess Charlotte of Wales was worn at her wedding to Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld in 1816 at Carlton House, London. HRP Textile Conservators Helen Slade and Libby Thompson recount the intricate conservation efforts taken to ready the dress for display.

Introduction

As a way of marking the Royal wedding in 2011, Historic Royal Palaces showcased their collection of six royal wedding dresses, spanning 150 years, to the international media. The oldest wedding dress in the collection, Princess Charlotte’s (1816), was conserved for the occasion, to allow for its one week display. More extensive conservation treatment in 2012 enabled its display in an exhibition at Brighton Royal Pavilion and Museum for the visiting public to enjoy.

Condition and Issues

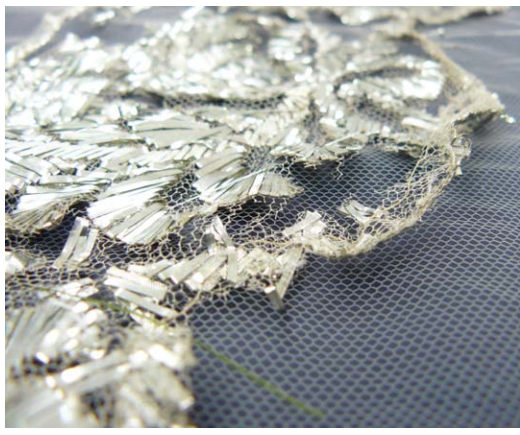

Princess Charlotte’s empire line wedding dress consists of five separate pieces, all of which have elements of silver within them, both cloth-of-silver and silk net embroidered extensively with silver lame. Although the silver is still remarkably untarnished, the silk net is brittle and deteriorated and has significant splitting due to stress from the weight of the embroidery.

The Dress on Display at Brighton Royal Pavillion and Museum

The dress had undergone two previous adhesive treatments to support the splitting silk net with nylon net: in 1969, and then in 1997 to reverse and re-treat the majority of the earlier work. The latter treatment is generally holding well. However the silver embroidered net trim on the cloth-of-silver train had not been re-treated in 1997. When the dress came to be treated in 2011, the 1969 treatment on the train trim was found to be failing.

It was hoped that the treatment devised for the failing adhesive on the train trim would inform the successful treatment of other objects in the collection having similar problems. This article focusses on the re-treatment of the train trim.

Investigations Into the Previous Adhesive Treatment

The entire border of the train had been adhered and stitched to a nylon net support in 1969, but the adhesive bond was now failing allowing fragments of silk net to curl up and become loose. There was also the risk that the adhesive could, over time, become increasingly tacky, stiff or irreversible.

The 1997 treatment records revealed that, where the earlier treatment had already been reversed, mechanical methods had been used and the support was replaced with a heat activated film of Vinamul 3252 (vinyl acetate, ethylene copolymer) on nylon net.

Aim

To ascertain whether a reversal of the 1969 treatment using solvent would put less strain on the object than any mechanical action to remove the previous support, and be more effective for full removal of the adhesive residue. The aim of the testing was therefore to formulate an effective way to reverse the 1969 treatment and remove any adhesive residues on the object if safe to do so.

Method

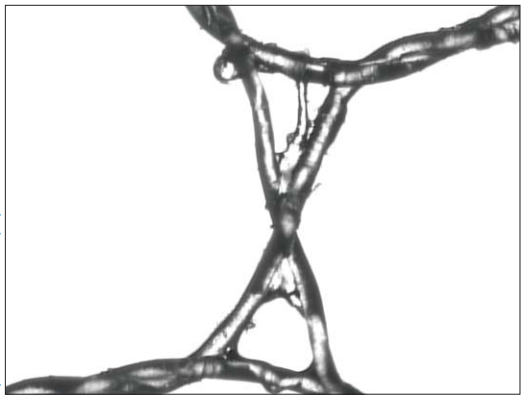

Fibres from both the support net and silk net were examined under high magnification which confirmed that an adhesive residue was still present on both textiles. The adhesive had a brittle, cracked appearance and was flaking off the fibres in places. As taking multiple samples of original silk net was not possible, further tests of the adhesive residue were carried out using only the previous nylon support net.

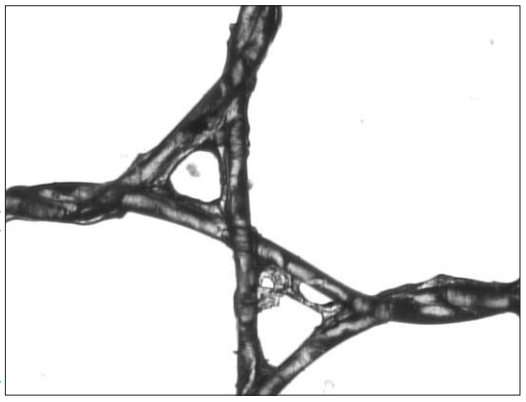

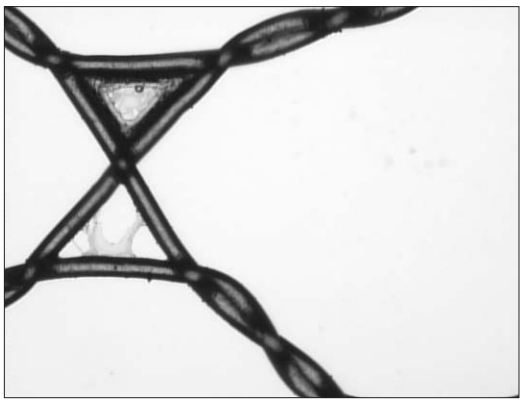

It was found that soaking the net samples in water caused the adhesive residue to swell but not dissolve. Soaking the net samples for twenty minutes in different solvents determined that 100% acetone was the most effective at removing the residue. This indicated that the adhesive used in the 1969 treatment had the characteristics of a PVAC adhesive.

Control Net With Adhesive Residue

However, soaking the object in acetone for twenty minutes as part of its conservation treatment was not a viable option. This was partially due to the limitations of the in-house facilities restricting safe extraction of solvent used on this scale; but also the potential effect the solvent would have on the silk net (acetone is known to potentially cause fibre desiccation).

Net After 20 Minutes Soaking in Water

Net After 5 Minutes Soaking in Acetone

Further tests were carried out using shorter time periods, without satisfactory results. Over a shorter period of time, the acetone appeared to cause the brittle and fragmentary residue to be re-deposited as a strong and coherent film, due to the solvent dissolution of the adhesive and its re-forming on the object; in effect re-activating the adhesive and, potentially, re-applying the adhesive rather than removing it.

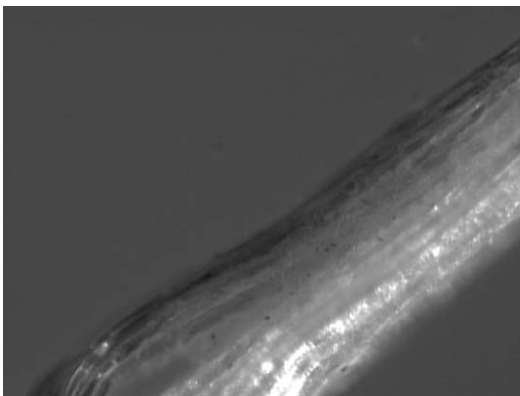

The Silk Net of the Object Showing the Starch Coating

Dripping solvent onto the samples was the technique tried next. The mechanical action of the dripping solvent onto the sample placed on a net above a petri-dish, rather than submerged, allowed the adhesive to be broken down and rinsed away. This proved an effective way to remove the adhesive residue, but only partially. It was felt that full removal of adhesive should be achieved if the fragile object was to be put through a solvent treatment.

As the adhesive was found to swell in water and dissolve in acetone, a technique that combined the two was considered. Testing showed that an effective technique was to drip water on the sample for three minutes to swell the adhesive and then drip acetone for five minutes to remove the adhesive and rinse it away.

This technique was then tested on a small sample of silk net from the object. However, unlike that of the nylon support net, this method did not remove the coating from the silk sample. To investigate this variable, a silk sample was soaked in acetone for twenty minutes, which also proved ineffective.

One 'Scallop' of the Trim Before Treatment Laid on New Conservation Net

It was therefore suspected that the coating on the silk net was different from the adhesive on the nylon net, and most likely an original finish of the silk. An iodine test showed that a strong concentration of starch was present on the sample, suggesting that the silk net had been stiffened with a starch-based finish.

One 'Scallop' of the Trim After Treatment

Conclusions

This starch layer made it very difficult to evaluate if there was a significant adhesive residue still present on the silk net and if the adhesive was being removed by the treatment. There was also the possibility that the starch layer could be damaged by the solvent. With this amount of uncertainty as to the benefit of an adhesive removal treatment, it was concluded that no solvent treatment should be undertaken on this part of the object.

However, the testing had been valuable in determining that the adhesive used was most likely a PVAC adhesive and also demonstrating that if not carefully tested, any attempted reversal of an adhesive treatment using a solvent may result in its re-activation and re-deposition causing more harm to the object.

Treatment of the Train Trim

As a solvent treatment was found to be inappropriate, an alternative mechanical method of removal needed to be found. Following the example of the 1997 reversal treatment, we decided that, with the adhesive already failing, mechanical action might be sufficient to remove the previous support. After investigation, the stitching holding the trim in place on the main body of the train was deemed to not be the original stitching and so removal of the trim would be appropriate and aid treatment. The placement of the trim on the train was fully documented before its removal.

Encasing the Trim

The silk net of the trim was in such poor condition that substantial conservation was needed. The 1997 adhesive treatment on the other parts of the dress had not been entirely successful, and additional stitching was required as well as net overlays in some places. Therefore an adhesive treatment was rejected in favour of encasing the trim in nylon net secured with stitching.

The effect that this could have on the drape and appearance of the trim was considered. However it was felt strongly that the trim would not withstand display without this treatment.

Appropriately dyed conservation grade nylon net was laid over the front face of the trim, with the grain of the silk and nylon net aligned, and then tacked in place. The piece was then turned over and the white cotton stitching from the 1969 treatment removed. The adhesive net support then peeled away easily leaving no tackiness to the touch. Creases in the trim were weighted and humidified using contact humidification.

A second layer of nylon net was then laid on top with the grain aligned and pinned in place. Each motif was stitched around with fine monofilament thread using running stitch; the tails of the threads were hidden within the embroidery. Small vertical lines were stitched in the areas between the floral motifs to control the net and give support.

Reattachment

The trim was placed on the train with the guidance of our documentation and stitched in place with a polyester thread. The stitching was applied where it would be unobtrusive and blend in with the embroidery.

Evaluation

Overall the treatment of the train trim was successful in providing stability to a fragile part of this historically significant wedding dress.

Testing showed that any solvent treatment undertaken would almost certainly have re-activated and potentially re-deposited the adhesive, making its removal far more problematic and damaging. Therefore, although the solvent testing did not result in developing a method for adhesive removal, it did demonstrate the risk of adhesive re-activation, information which will inform future treatment strategies for the collection.

Overall, the amount of uncertainty in the value of a solvent treatment on such a fragile object could not justify its implementation. The previous support could be easily removed mechanically due to the failure of the 1969 adhesive treatment and no tackiness could subsequently be detected on the object. Additionally, having the opportunity to examine two previous attempts to treat the object using adhesives and assessing their long-term viability led us back to choosing a stitch-based treatment.

The Dress on Display - Reverse View Showing the Trim on the Train