Holding more than 13 kilometres of physical records, the UK Parliamentary Archives dates back to 1497 and includes many of the UK’s most important constitutional records, including the Bill of Rights, the 1832 Great Reform Act, and the Death Warrant of Charles I. Although the collection is predominantly parchment and paper-based, we do occasionally come across an oddity within the repositories, such as the Tracy gravestones.

The story of the stones

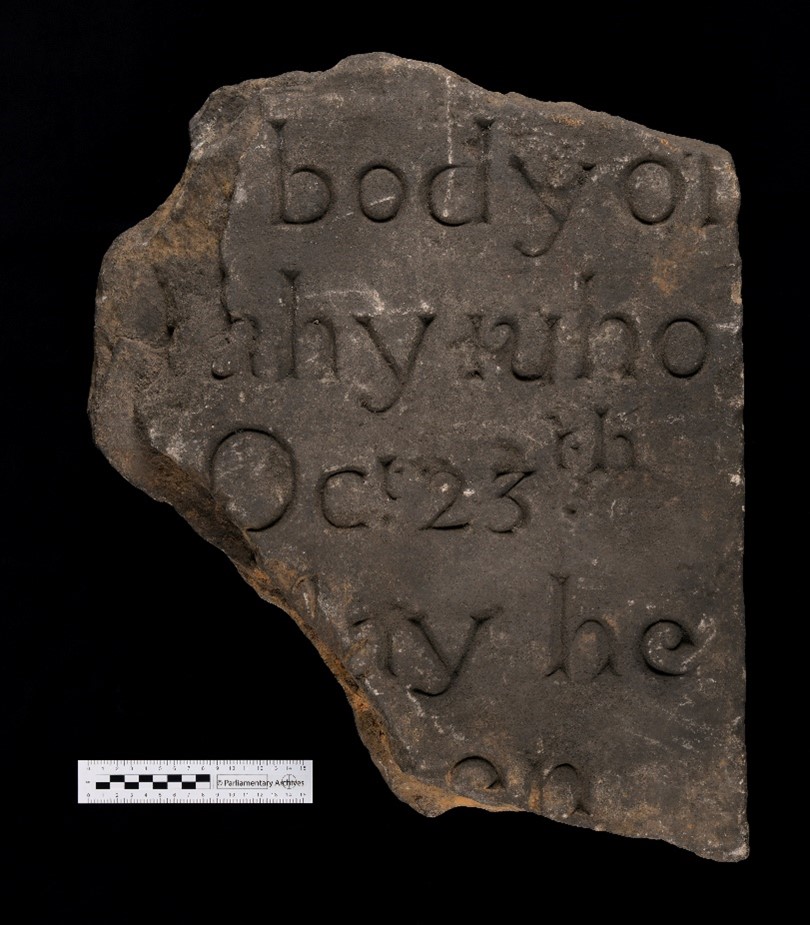

The Tracy gravestones are a collection of 24 stone fragments, taken into the Parliamentary Archives after being submitted as evidence in a peerage claim by James Tracy in 1845. The authenticity of the stones was questioned in 1847/48, with a witness named Patrick Holton claiming that he had been employed to carve, break and artificially age the stones. This claim was never formally resolved, however, so the stones have retained an air of mystery ever since.

Above: Digital images were taken of each gravestone fragment, allowing for clear identification and easier access for future research

Preparation is key

In preparation for a collection move out of the Palace of Westminster’s Victoria Tower, the Parliamentary Archives Collection Care Team (PACC) has been working alongside the Archives Relocation Programme’s project teams to carry out a huge amount of auditing, treatment and packing.

The Tracy gravestones were highlighted to PACC as requiring significant rehousing before they could begin any move. The largest fragment – almost a full gravestone – had been previously crated, separate from the rest of the collection. However, the other 23 pieces were untouched.

Having been stored in the original wooden crate they had arrived in more than 100 years ago, the stones were open to environmental fluctuation and dust, had no protection, and were generally difficult to manoeuvre. They therefore required a new housing solution that would provide increased security, stability and longevity, with a focus on long-term storage and future access. As Senior Conservation Technician, I was brought in to provide specialist packing advice and project coordination, to ensure all fragments were safe to be handled, stored and digitised. At completion of my role in the project, the stones were handed over to the project’s Moves Team, who manage the transport of collections off site.

The first step in figuring out a packing solution was to gather as much visual, physical and contextual information about the stones as possible. I consulted several specialists, who could provide various perspectives on both the materiality and future use of the stones.

Once I had a clearer vision of the information and preparation needed, I set up a working session with the Parliamentary Archives Imaging Team and the Archives Relocation Programme’s Project Conservator. Collaboration with the Imaging Team was crucial, as the fragments had no previous digital record. Being heavy to move and difficult to retrieve, this meant they were practically inaccessible. Similarly, working with the Project Conservator was critical to ensuring that correct materials, tools and techniques were used. This would keep the safety and longevity of the stones at the forefront of the project.

Above: A gravestone fragment being gently dusted

During the working session, each stone fragment went through several steps. First, the fragment was lightly brushed to remove the finest layers of dust. Because of the potential presence of historic ‘forged’ surface dirt, it was important to work gently. The fragment was then imaged in high-resolution, to capture any carving or surface details. The fragments’ general condition, weight and dimensions were recorded, and a template of each stone’s footprint was made to assist with packing designs later. Finally, a catalogue number was assigned to each fragment and labelled directly onto the stone by the Project Conservator, using paper labels and Paraloid B72.

Above: The general condition, weight and dimensions of each gravestone fragment were recorded

Following this workflow, all 23 stone fragments were processed over a total of two working days. Several useful outcomes were produced from this one session alone, including multiple high-resolution images and a database of physical condition data. With the heaviest fragment weighing in at 27.25kg, this was essential information to record for the future safety of both the stones and researchers!

The packing solution

Of the 23 fragments, 10 pieces were of a significant size and/or weight. Keeping all 23 fragments together would continue the previous issues with access and moving, so I decided to separate the 10 pieces for handling purposes. Consulting with the Moves Team, we decided that they would be packed individually by the Project Team, directly onto pallets for transit. I deemed the remaining 13 fragments small enough to be grouped and packed together. This would ensure they stayed secure and protected during transit. Using the weight and overall footprint of each fragment as a guide, I separated the 13 small pieces into two groups for packing. Each group weighed less than 8kg, a much more manageable carrying weight.

I chose to use Utz containers to house these two groups of small stones, because of their strength and ability to be stacked. These bins were filled with inert Ethafoam layers, creating a deep base into which bespoke cavity mounts were then carved for each specific stone shape. Finger cutouts were included in each shape, to allow for easy handling in and out of each cavity. Tyvek was then used for lining, providing a neutral barrier between the surface of each stone and the texture of the Ethafoam.

Above: Smaller gravestone fragments were grouped and packed together in Utz containers filled with Ethafoam and the bespoke cavities lined with Tyvek

Packing and handling instructions were also added to each Utz container. Instructions included wearing gloves when handling, using two hands to hold each fragment and being careful not to disturb too much of the ‘historic’ surface debris, which is linked to the stones’ potential forged past. A visual key was also prepared to help identify each fragment from its position within the container. This key would also ensure that users in the future can retrieve and repack the stones with ease. The final step was to attach the new catalogue numbers to the outside of each container and apply a barcode to track the location of each box for moving.

All pieces of the Tracy gravestones were reunited on move day, as they were prepared and loaded onto the moving lorry. The 10 pieces passed onto the Moves Team were wrapped in Tyvek, placed onto a Plastazote layer and strapped directly down onto wooden pallets using cotton webbing. The largest crated piece was then loaded, alongside the two newly packed Utz containers. The only remaining step was for the gravestones to head off to storage in their new safe and secure housing.

On reflection

This project was a great opportunity for me to take on responsibility for the planning, organisation and design of a project, while occupying a pivotal technician role. The initial brief – to prepare the stones for transport – quickly evolved into a much larger project that required input and collaboration with teams from across the Parliamentary Archives. I found that communication and flexibility were key, and I’m glad we could build in the opportunity to gather additional condition information, take images, and add to the catalogue as part of this project. The images of each fragment are now able to be accessed online, allowing for clear identification and easier access for future researchers. Meanwhile, the physical data and condition information can continue informing the stones’ future storage and handling.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Connie Search is the Senior Conservation Technician at the UK Parliamentary Archives, specialising in the housing and display of collection items. She has a background in fine art and is a trained bookbinder with experience in historical and contemporary binding styles. In the past she has worked with the Charles Dickens Museum, The Royal Philatelic Society and Gunnersbury Park Museum. She currently volunteers with Dacorum Heritage Trust and is completing an MA in Museum Cultures and Collections Management at Birkbeck, University of London