During the re-cataloguing of the Prize Papers collection at The National Archives, Kew, the provenance of 200 closed letters couldn’t be determined, so I was asked to open them.

The Prize Papers is a collection of seized papers and goods found on enemy ships captured by the British during wartime (c.1652-1856). The Prize Papers are being digitised in partnership with Oldenburg University.

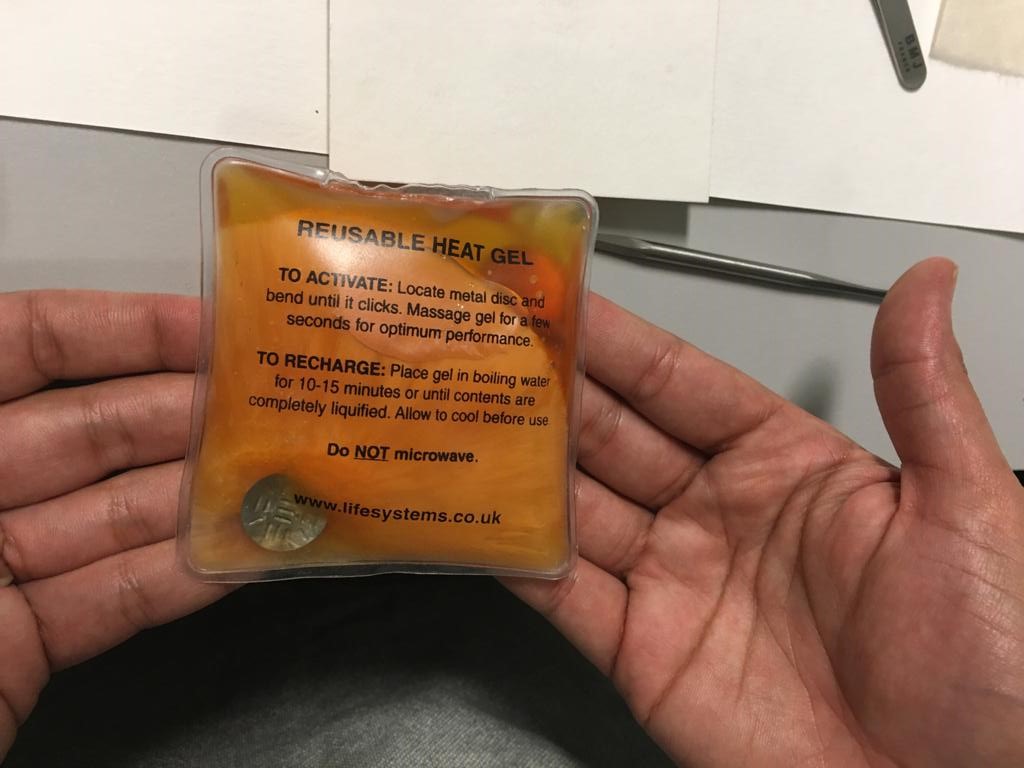

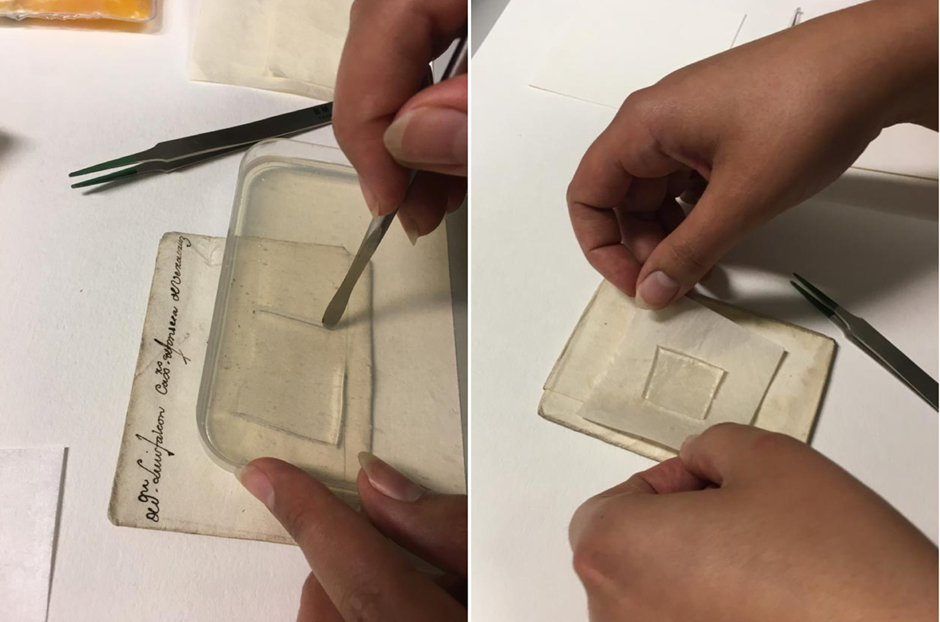

Using an agar gel impregnated with an alpha amylase enzyme, I was able to open letters sealed by starch-based wafer seals whilst preserving blind embossing and minimally altering the aesthetic of the letters.

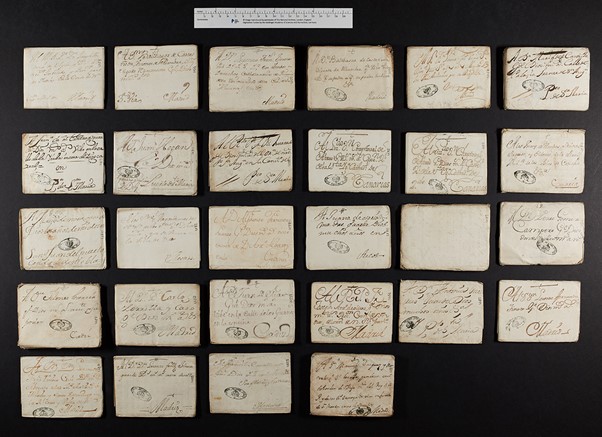

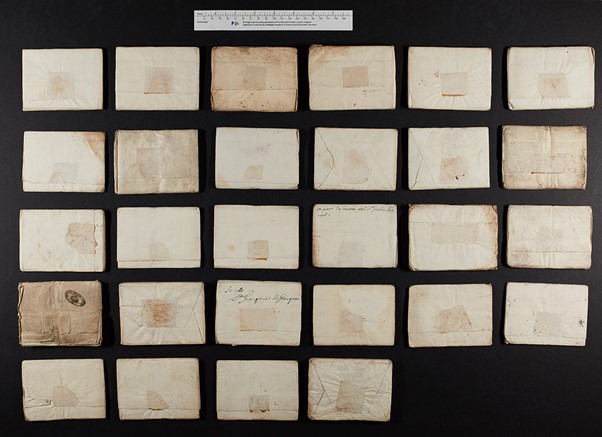

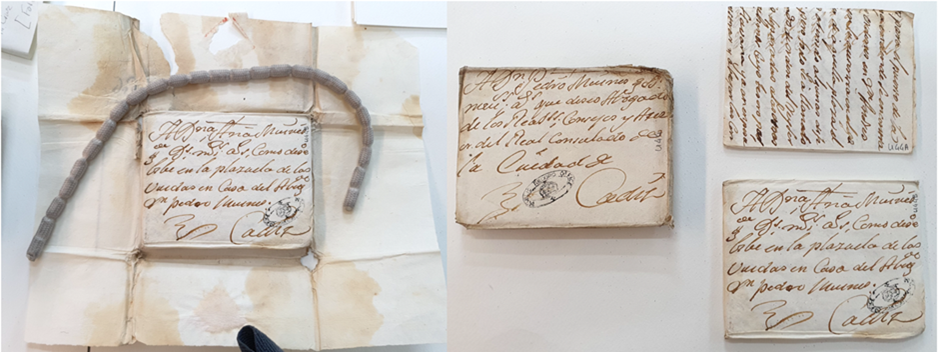

The closed letters

The letters could have come from either the Fort de Nantes captured in 1747 or the Atrevida captured in 1779.1 About 5% of closed letters in the collection make a reference to the ship that carried them, written on the outside. For the rest of the closed letters there is often no other way to identify their provenance, which ship they came from and when they were written, unless the letter is opened and read (Bevan, A., and Cock, R., 2018).

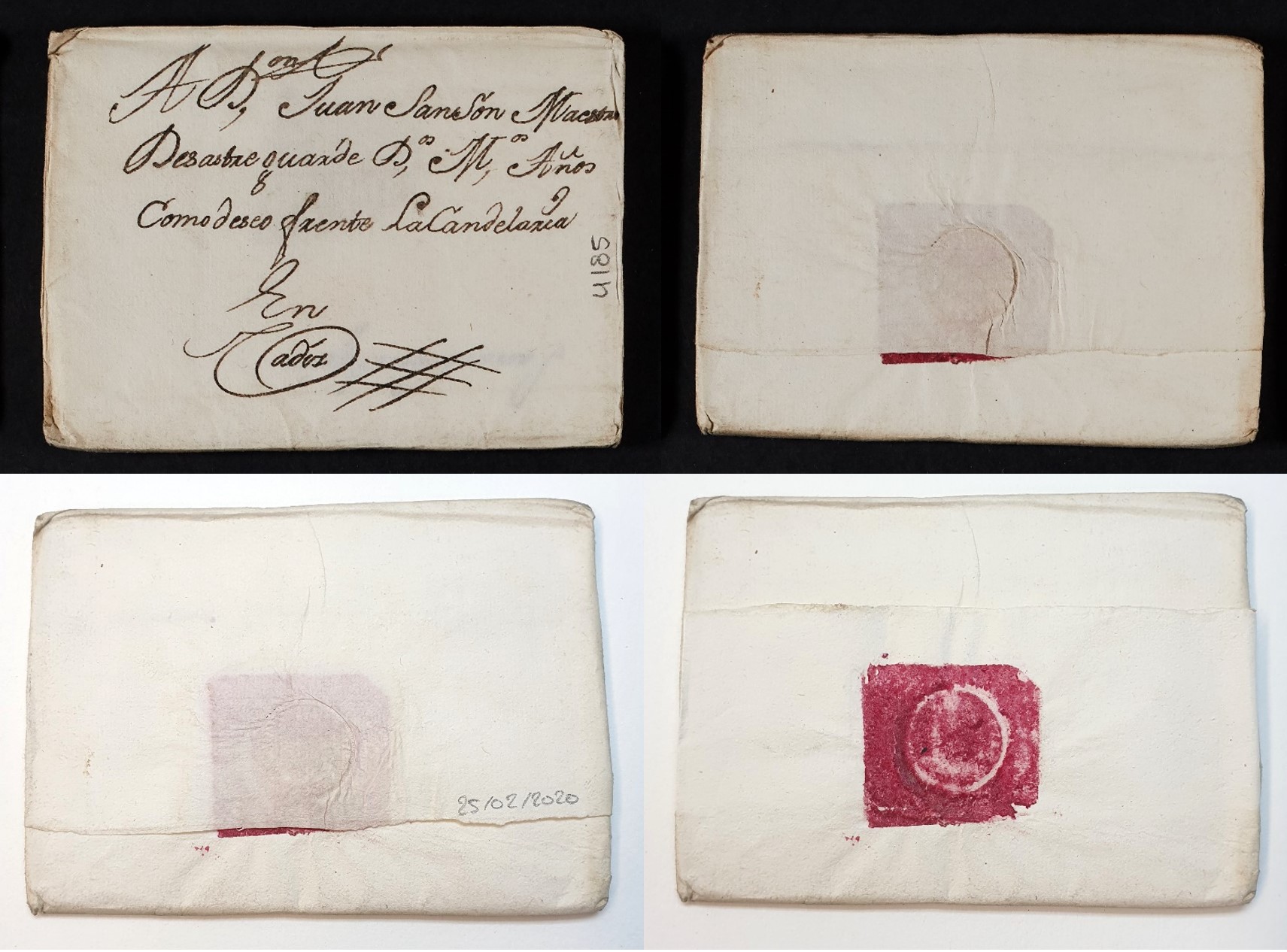

Documentation photographs were taken to record the appearance of the letters prior to opening.

Seal analysis

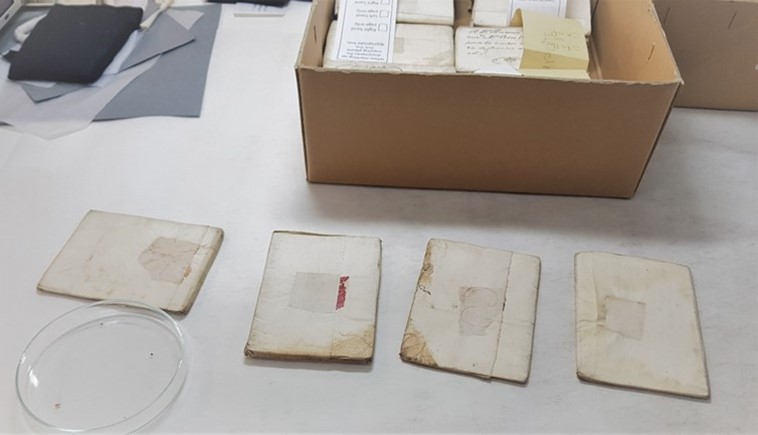

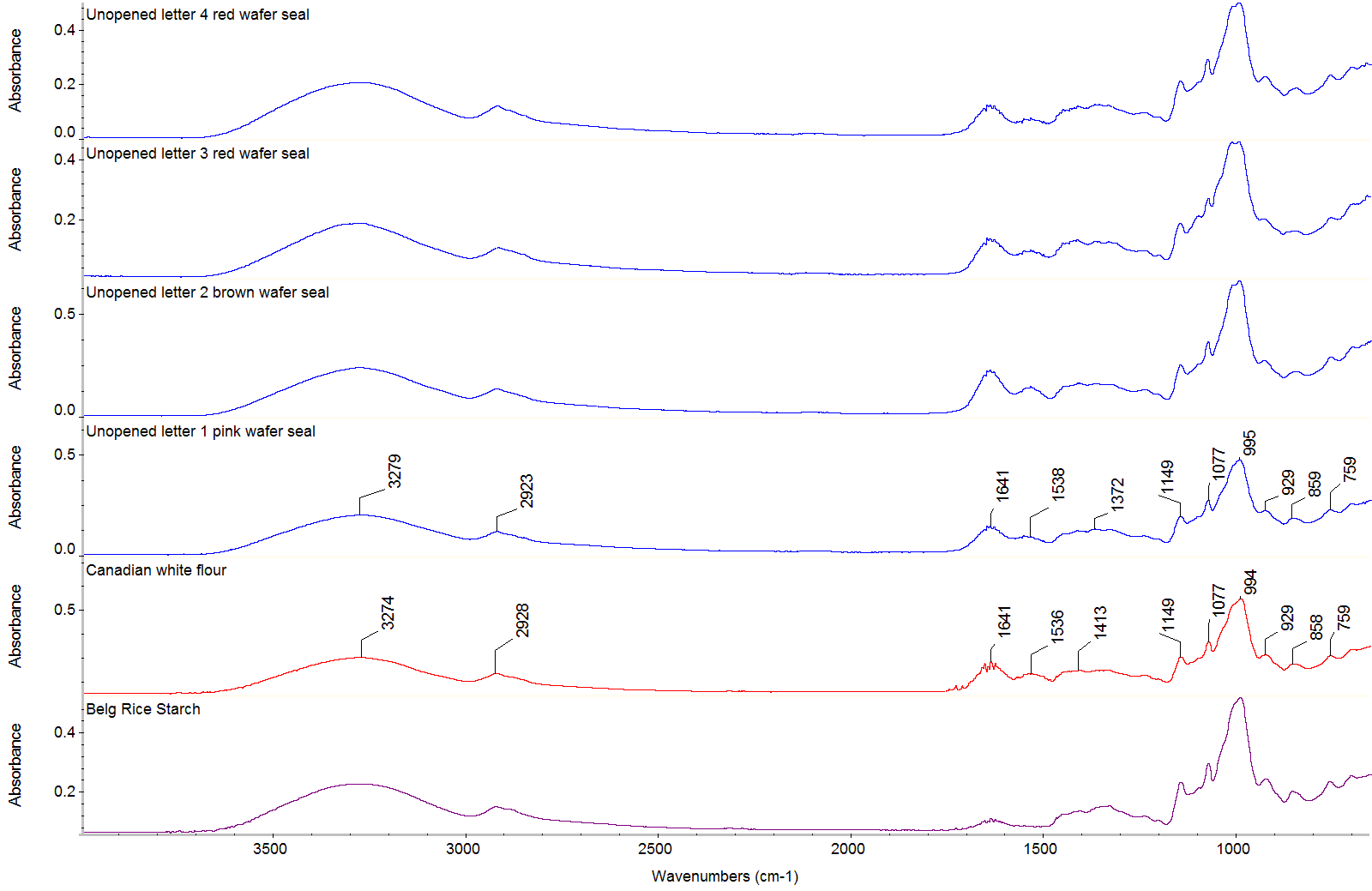

Before testing, I identified 3 potential groups of seal materials: shellac seals, brown wafer seals and, pink or red wafer seals. This blog focuses solely on the opening of the wafer seals. Letters with shellac seals were carefully cut open using a scalpel, preserving as much of the physical materiality of both the seal and the letter as possible.

Four letters were used for ATR-FTIR testing and, regardless of colour, ATR-FTIR showed the wafer seals were all starch-based. On this basis, I opted for an alpha-amylase enzyme-based treatment to open the letters (Borring et al., 2015).

Following analysis, I sorted the letters by sealing mechanism and numbered them so they could be imaged before I began treatment. The pre-treatment imaging is a key part of the Prize Papers Project as it helps us record all original materiality within the collection.

Table 1: Breakdown of number of letters according to closure mechanism after ATR/FTIR testing.

|

Number of letters by sealing material/mechanism |

|||

|

|

Box 1 |

Box 2 |

TOTAL |

|

Red/pink starch wafer |

25 |

32 |

57 |

|

Brown starch wafer |

61 |

87 |

148 |

|

Shellac seal |

4 |

|

4 |

|

Tuck and fold (not sealed) |

15 |

22 |

37 |

|

Tied bundle |

|

1 |

1 |

|

TOTAL |

105 |

141 + 1 tied bundle |

246 + 1 tied bundle |

Previously opened letters have often contained secondary letters - like letter U44 in Figures 5 and 6. As most were written in iron gall ink, using a gel to introduce the enzyme seemed like the safest way to separate the starch wafer from the letter wrapper using minimal moisture, which protected the iron gall ink from possible corrosion (Cremonesi, P., 2013.).

Treatment experimentation

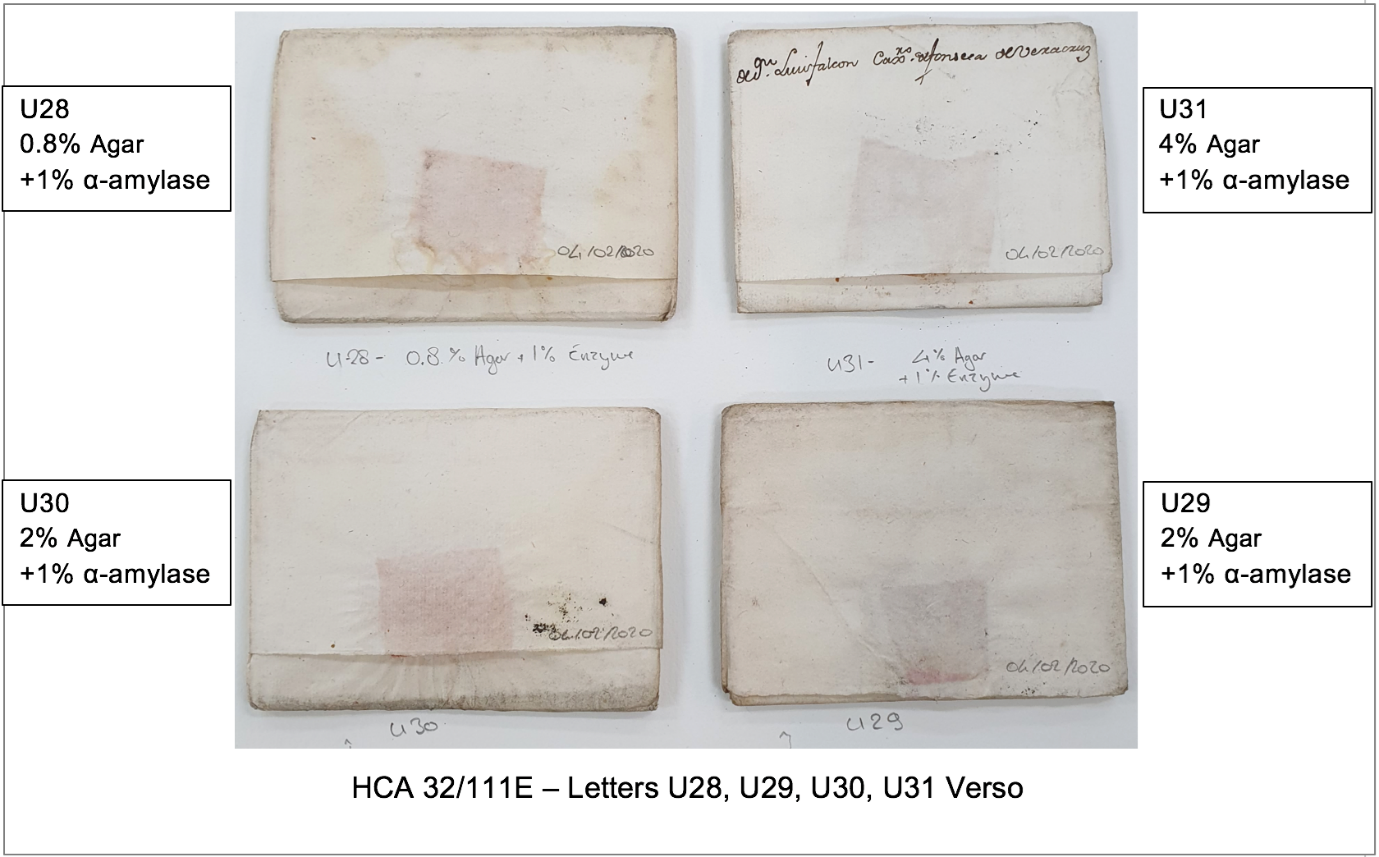

Table 2: Results of experimentation with agar gel and α-amylase agar gel.

|

Results of experimentation with agar gel and α-amylase agar gel |

||||

|

Letter number |

Agar gel Concentration (%) |

α-amylase enzyme concentration (%) |

Observations |

|

|

U28 |

0.8% |

1% |

|

|

|

U29 + U30 |

2% |

1% |

|

|

|

U31 |

4% |

1% |

|

|

|

U32 |

4% |

N/A |

|

|

As the intention was to cause as little visible change in the treatment area of the closed letters, I chose to go with the 4% agar gel with 1% α-amylase liquid enzyme.

The enzyme gel acted quicker on the more pigmented red/pink wafers, whilst brown wafers took longest to ‘open’. It is likely the wafer seals with a red or pinkish hue may contain a lower concentration of starch due to the addition of red pigment. The thickness of the paper and the wafer will have also affected the penetration of the enzyme into the desired area.

With this method I was able to facilitate access to the documents without jeopardizing any material features as can be seen in the picture below.

Useful links

- Visit The National Archives’ records catalogue to find out more about the letters

- Learn more about the Prize Papers Project

Key references

Bevan, A. and Cock, R. (2018) High Court Admiralty Prize Papers, 1652-1815: Challenges in Improving Access to Older Records, Archives. Vol 53(no.137), 34-58.

Jana Dambrogio, Daniel Starza Smith, and the Unlocking History Research Group. 2019. Dictionary of Letterlocking (DoLL). Last updated: 30 December 2017. Date accessed: [08.07.2020]. Abbreviated on this page: (DoLL 2016). All images except when noted are courtesy of the Unlocking History Materials Collection. http://letterlocking.org/dictionary

Borring, N., Hilby, C. (2015). ENZYMES IN CONSERVATION Separating the Triumphal Arch by Albrecht Dürer with α-amylase embedded in Agarose gels. 10.13140/RG.2.1.1505.1609. Link to poster: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286354632_ENZYMES_IN_CONSERVATION_Separating_the_Triumphal_Arch_by_Albrecht_Durer_with_a-amylase_embedded_in_Agarose_gels

Cremonesi, P. 2013. "Rigid Gels and Enzyme Cleaning." in New Insights into the Cleaning of Paintings: Proceedings from the Cleaning 2010 International Conference, Universidad Politecnica de Valencia and Museum Conservation Institute, edited by Mecklenburg, Marion F., Charola, A. Elena, and Koestler, Robert J., 179–183. Smithsonian Contributions to Museum Conservation. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. Link to article: https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/20507/29.Cremonesi.SCMC3.Mecklenburg.Web.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Markevicius, Tomas & Syversen, Terje & Chan, Emma & Olsson, Nina & Hilby, Carola & Šimaitė, Rytė. (2017). Cold, warm, warmer: use of precision heat transfer in the optimization of hydrolytic enzyme and hydrogel cleaning systems. Link to article: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313470845_Cold_warm_warmer_use_of_precision_heat_transfer_in_the_optimization_of_hydrolytic_enzyme_and_hydrogel_cleaning_systems

Van Dyke, I., “Practical Applications of Protease Enzymes in Paper Conservation”. 2004. The Book and Paper Group Annual 23 (2004) 93.

Link to article:

https://cool.culturalheritage.org/coolaic/sg/bpg/annual/v23/bp23-16.pdf

Image copyright

All images produced by the Prize Papers Project, funded within The Academies Programme of the Union of the German Academies of Sciences and Humanities, assigned to the Academy of Sciences and Humanities in Göttingen, based at the Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg, Germany, and the UK National Archives, London. Reproduced by permission of The National Archives, London, England. Images may be used only for purposes of research, private study or education.

Camilla was born and raised in France. She studied History of Art at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts in Birmingham before moving on to Conservation at Northumbria University. Camilla spent 4 years at The National Archives working predominantly on the Prize Papers project. She now has a private practice in Conservation of Art and Archives on Paper.