At the Smithsonian Institution’s Libraries and Archives, conservation efforts are dedicated to preserving important historical documents and enhancing access to the rich and diverse recources in its care. One such project involved the delicate restoration of a field notebook belonging to the French scientist Constantine Rafinesque. This unique item, with its multi-directional writing, required an intricate and thoughtful conservation approach to ensure both its physical integrity and accessibility for researchers. Through a combination of careful mending, binding, and innovative techniques, the notebook has been brought back to life, offering valuable insights into Rafinesque’s work and scientific contributions.

As a child you could always find me with a book in hand (and honestly, this is often true of me as an adult). It’s perhaps not surprising, then, that when choosing my profession, I gravitated to conservation of books and paper! In my work at the Smithsonian Institution’s Libraries and Archives, much of my conservation work is devoted to allowing patrons and researchers to access these physical items again—and in the case of the project I will describe here, to simply understand the contents of the book I have been treating.

Rafinesque's Field Journal

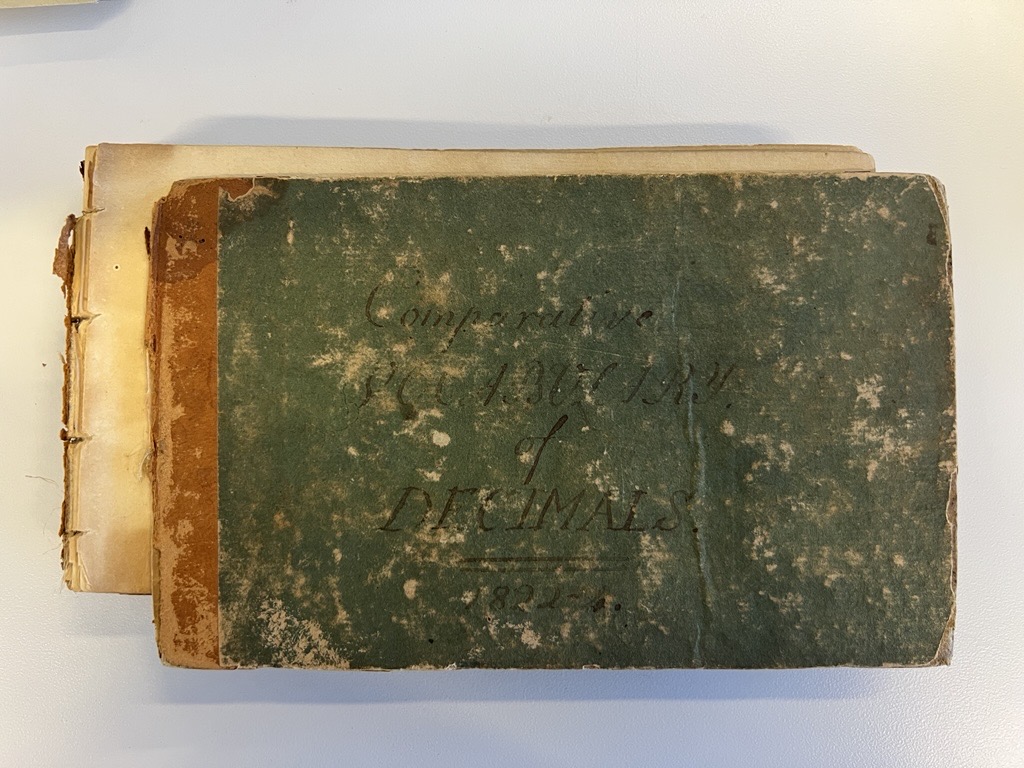

The item in question is a field notebook or journal, a stationery binding used by field or collecting scientists to record information about specimens collected and, in many cases, context to their travels. This field notebook belonged to French scientist Constantine Rafinesque, a contemporary and acquaintance of ornithologist John James Audubon, and the volume is evidence of his wide-ranging interests and expertise, for he recorded data about two different topics—writing in the book first from the front and then flipping it upside-down and recording from the back for another topic.

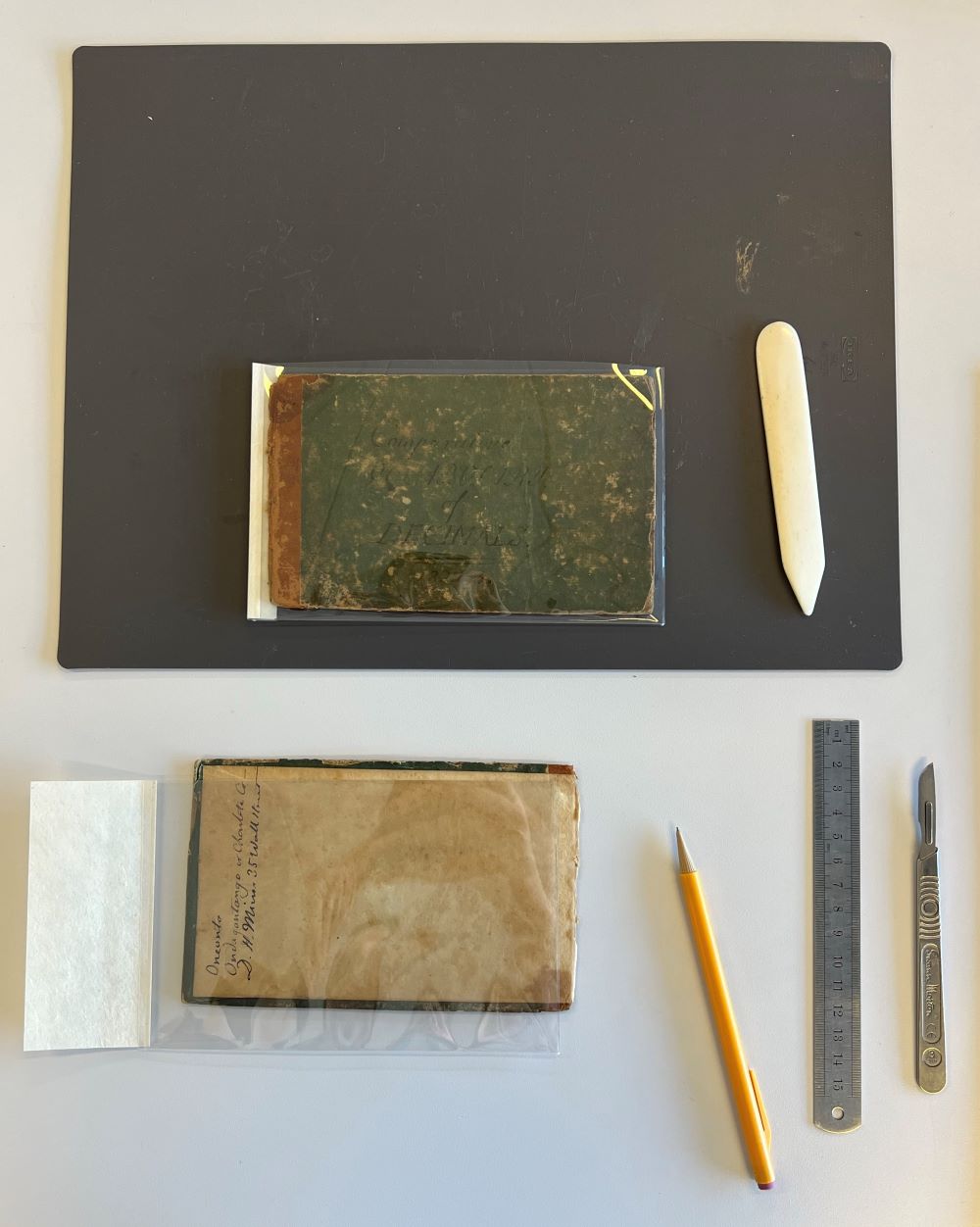

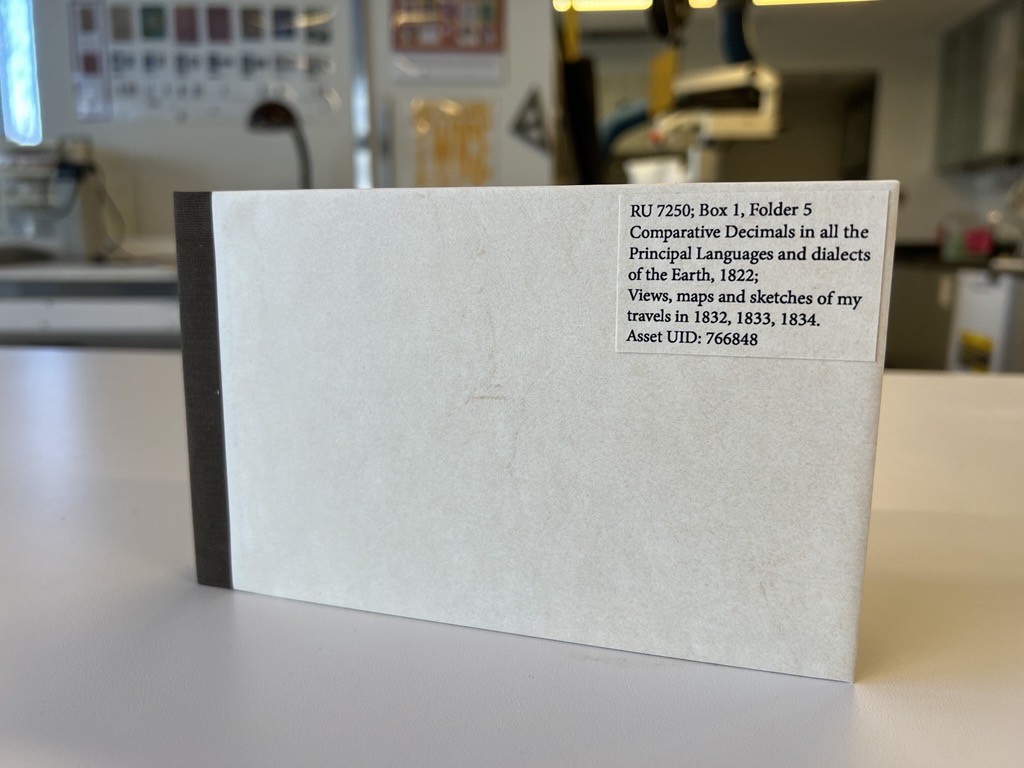

Figure 1. The Rafinesque notebook before treatment; the leather’s poor condition is evident on the detached cover board.

Reconstructing the Journal, an Intricate Puzzle

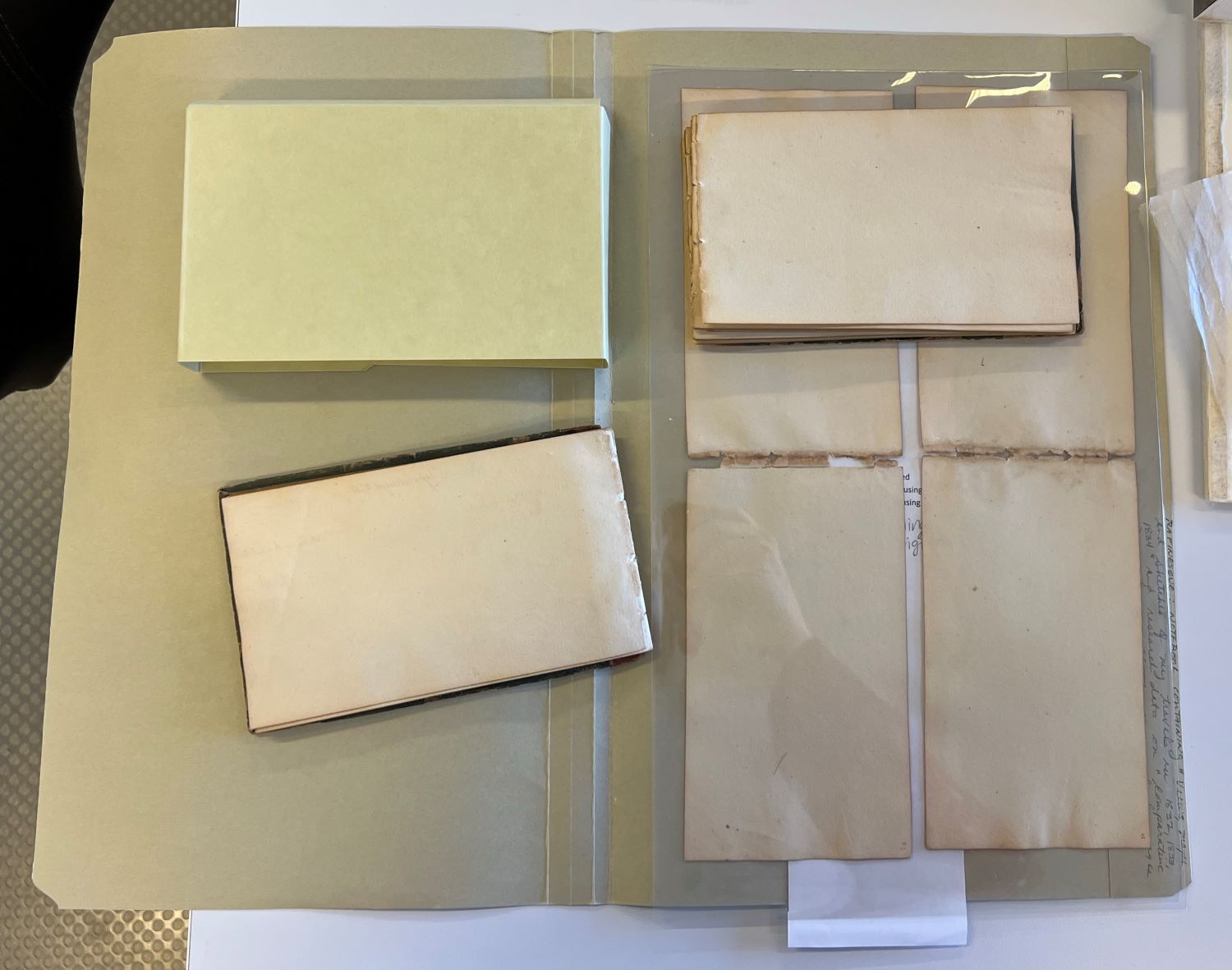

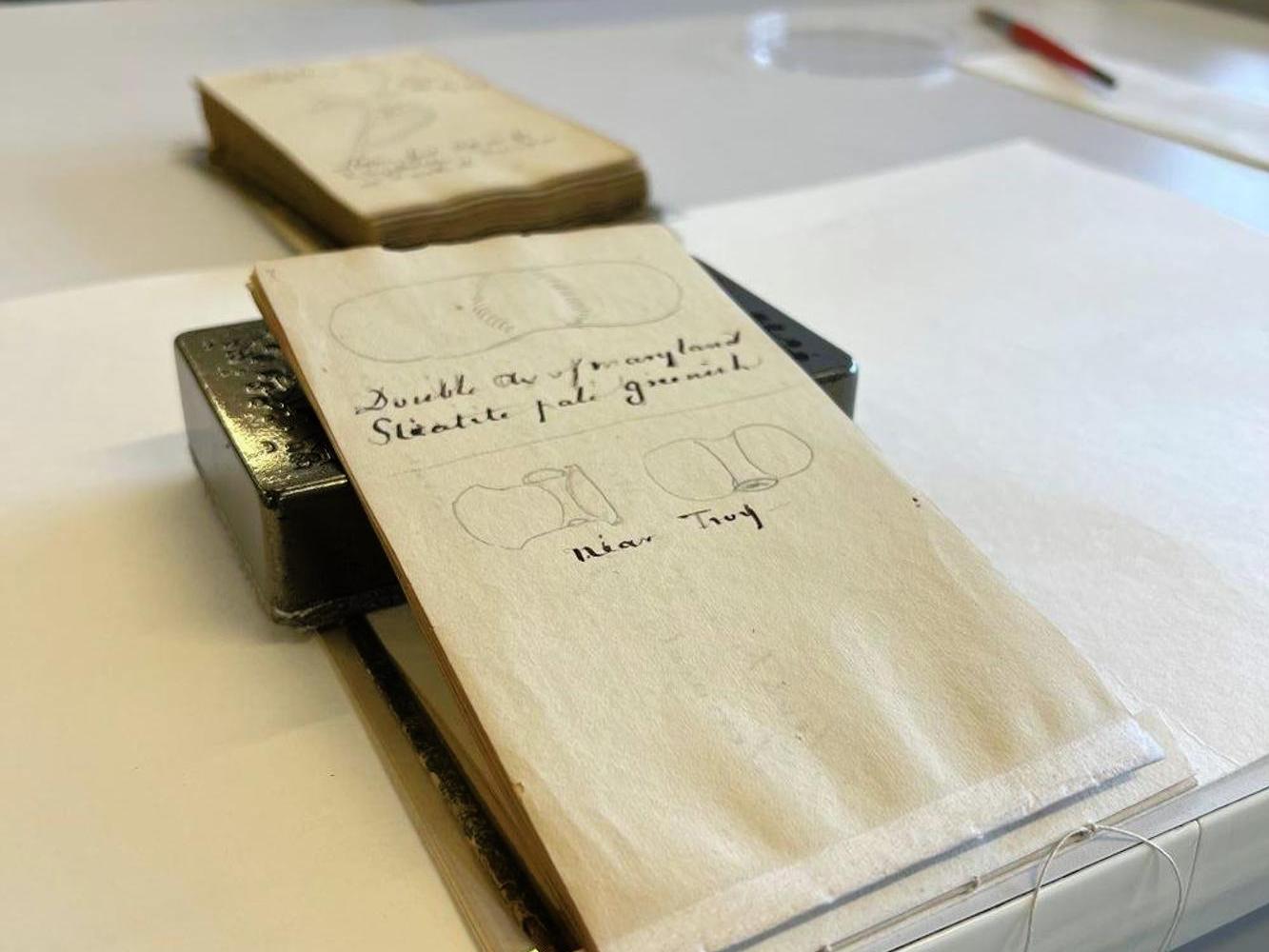

When it came time to treat the volume, this multi-directional use became especially important when I discovered the book to be in multiple pieces, which had been stacked back together out of order. Physical clues helped me piece together what I believe to be the correct order of pages—the location of sewing holes from the book’s original binding structure, offset of ink or other media from one page to a facing one, and staining from outdoor use, as well as edge distortions of the pages due to fluctuating humidity over the decades since the book was first bound. I created a collation diagram, a schematic showing where each page belonged, and lightly numbered each page with a soft pencil to ensure that the recreated order was maintained.

Figure 2. Partway through separating, sorting, and mending the out-of-order pages. Orphaned folios were gathered in Mylar sleeves to help prevent further dissociation.

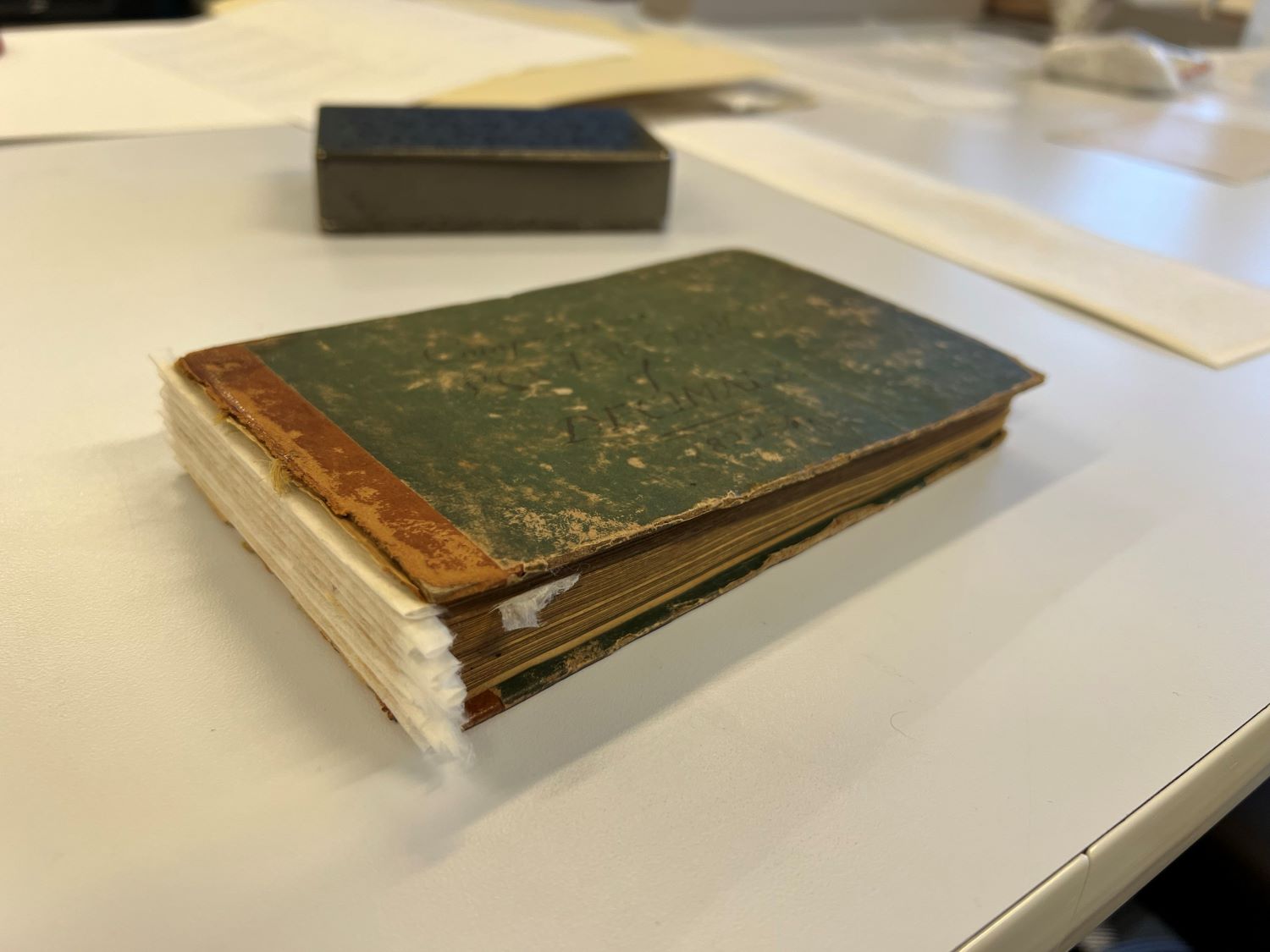

Many of the book’s gatherings were still intact, but not all, and so I took a measured approach to mending the pages and guarding the spinefolds. Guarding refers to strengthening or reinforcing the folds of pages with Japanese paper and wheat starch paste, and this was done to help balance stresses on the new binding and preserve the original structure as much as possible. Because of the amount of guarding needed, I used a Japanese paper with prepared tear lines to help reduce the amount of time required to create consistently sized pieces .

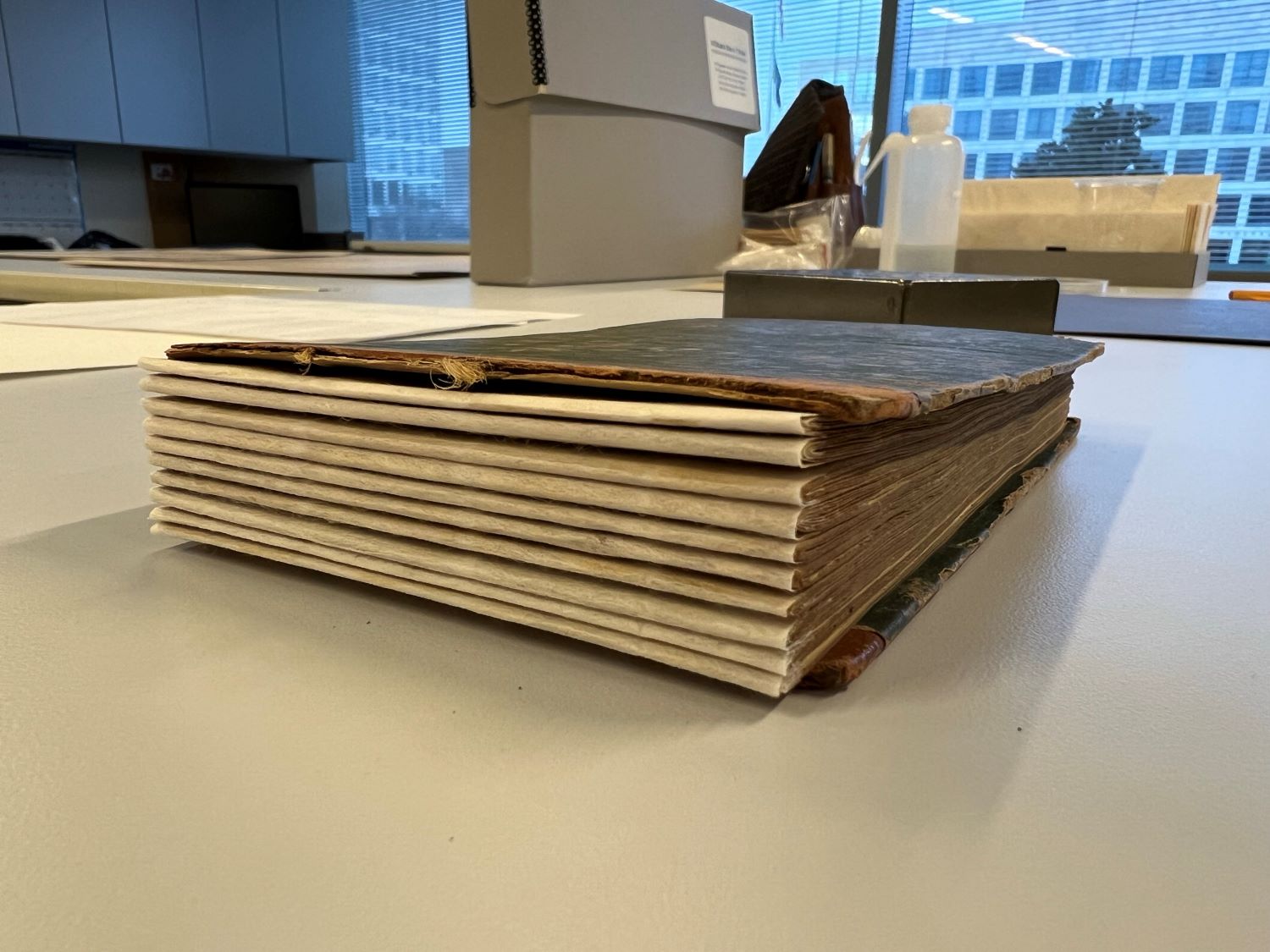

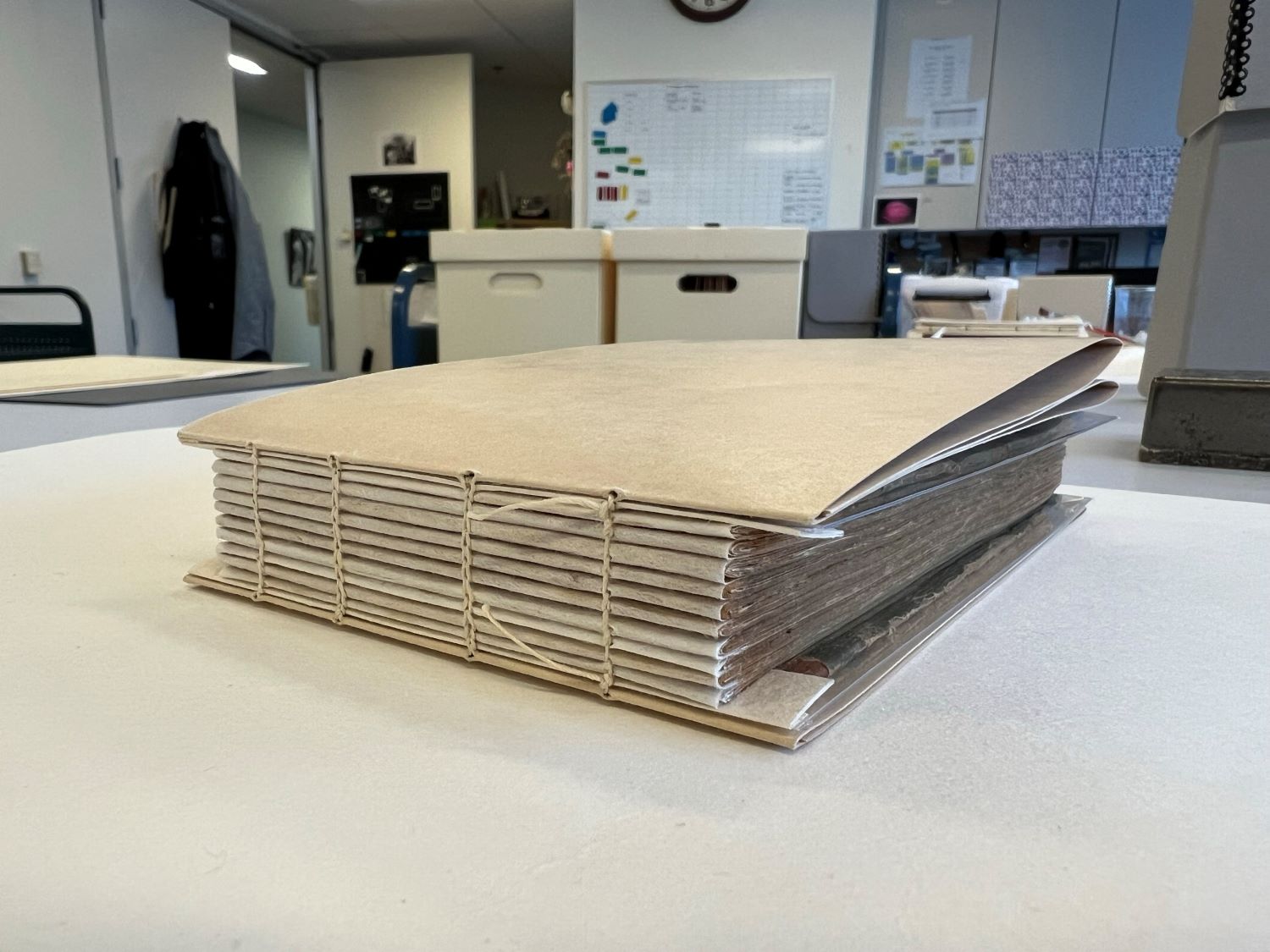

Figure 3. The field book after guarding and mending was completed, with Japanese paper protrusions awaiting trimming.

Figure 4. The spine of the field book after all guards and mends were trimmed. The discrete gatherings of paper are clearly visible and distinct.

Reviving Traditional Binding Techniques

Our stationery bindings are usually treated according to standard operating procedures or pre-planned workflows, and with these field notebooks, we often make use of the sewn boards binding, a conservation structure pioneered by conservator Gary Frost, that borrows ancient cover attachment techniques from traditions including Coptic bookbinding. In a sewn boards structure, folios of cardstock are sewn into the structure as outer gatherings of the book, creating a strong, integral attachment and requiring little wet adhesive to finish the binding.

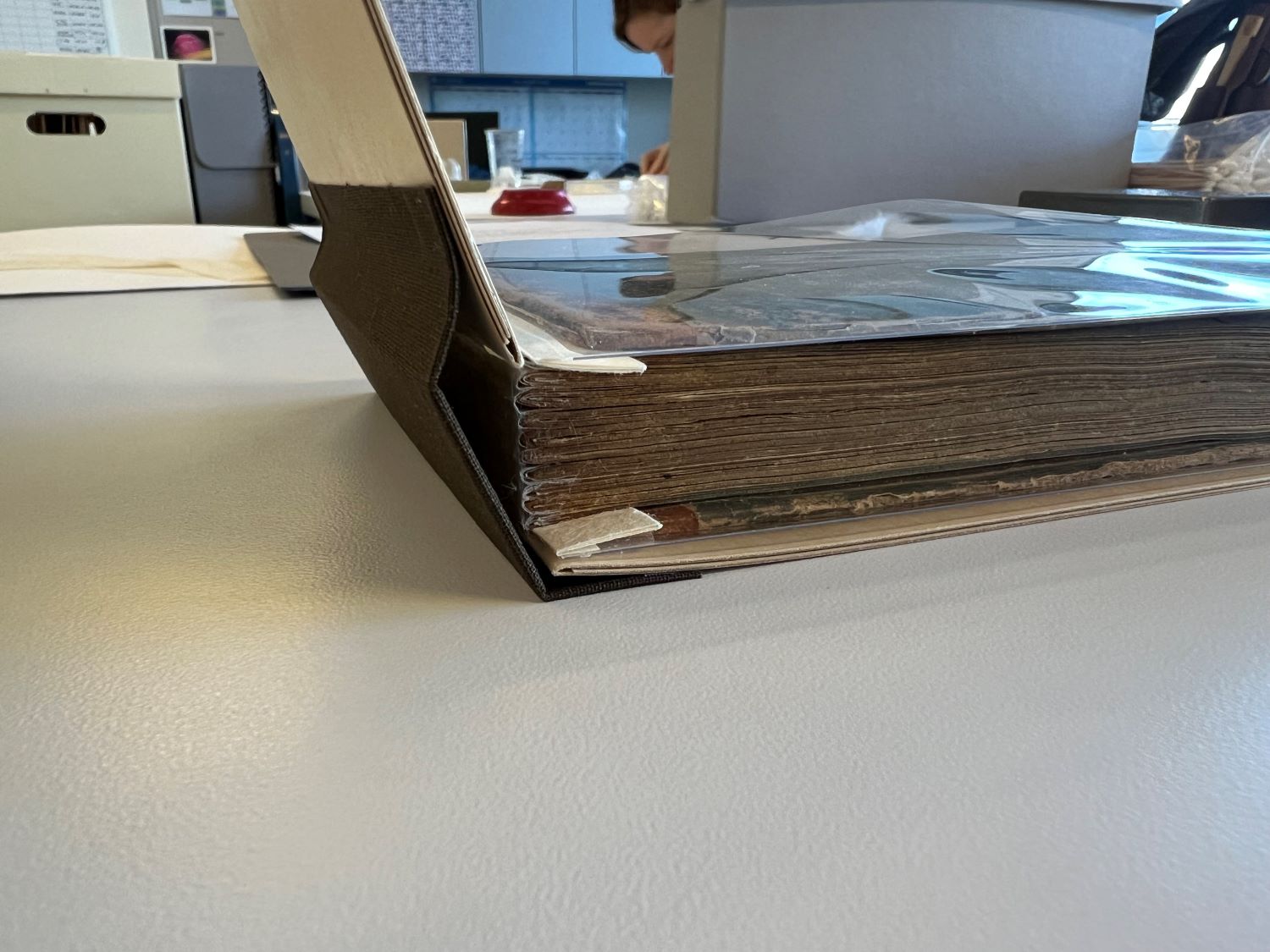

A sewn boards structure is sometimes used when covers are missing, but our stationery bindings often have covers that are present but no longer attached, and there are several possible options for including these detached covers in this new structure. Recently, I have been incorporating the detached covers or boards by placing them into Mylar pockets, attached to Japanese paper hinges via ultrasonic welder to allow these pocketed covers to be sewn directly into the structure as well. I had seen a colleague (Ashleigh Ferguson Schieszer of the Cincinnati and Hamilton County Public Library, Ohio, USA) do something similar with pages of a Jewish Haggadah at the American Institute for Conservation’s 2024 Annual Meeting, and thought I could borrow it for this purpose. While the welds can be delicate, and the thickness of the cover boards sometimes encourages the Mylar to pop off the Japanese paper, the finished product looks as similar to the original structure as it could, considering the interventions taken, and the boards sit against the book’s pages in almost perfect alignment.

Figure 5. Preparing the Mylar pockets for the acidic cover boards. One completed pocket is visible on the gray cutting mat, while the second is having the fit checked before finalizing the component.

The simple link-stitch sewing begins from one of the cardstock folios, passing next through one of the cover board pocket’s Japanese paper hinges, folded into a double thickness for increased robustness, and then into the gatherings of book pages, before finishing through the other cover board pocket and cardstock folio (see Figure 6, Figure 7). A pair of Japanese paper spine linings were applied, one as a reversibility layer and consolidant, and another to control the opening of the book.

Figure 6. Shortly after beginning the sewing of the volume in a sewn boards style. The gatherings awaiting inclusion are visible in the background.

Figure 7. After sewing was completed, from the spine, with the multi-thickness cardstock folios visible, gaping slightly.

Covering was done without wet adhesive, using archival double-sided tape to laminate the cardstock folios into a layered cover board; a spine was created from bookcloth, stiffened with more cardstock, and the remainder of the boards were covered with Zander’s elephant hide paper, finishing with a label describing the item.

Figure 8. Partway through covering, with the cloth spine attached, showing the opening action.

Figure 9. Nearing completion of the covering stage, with the trimmed paper covering pieces adhered to one laminated cover board and awaiting attachment on the other

Figure 10. The completed volume with descriptive label visible.

The Importance of Treatment

This treatment was important for a variety of reasons. Pure preservation is certainly at the top of the list—without this treatment, the book would have continued to deteriorate further as the broken elements abraded each other, or vulnerable pages were creased or broken in the same manner. Treatment also facilitated digital imaging for broader access. However, the content benefited as much as the physical object did. The damage to the structure caused confusion in reading and understanding the content of Rafinesque’s notes and observations. With the book restored to order, physically and conceptually, anyone looking to read the volume can do so without difficulty.

Figure 11. The completed volume, showing one of the picturesque landscape sketches from Rafinesque’s notes.

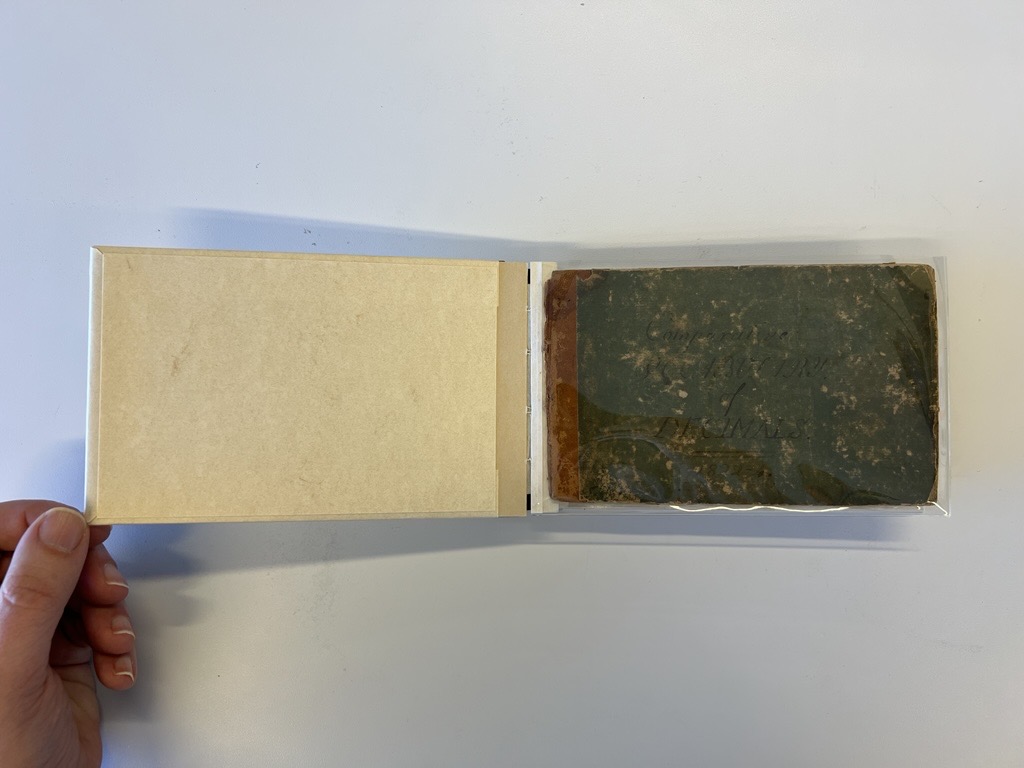

Figure 12. The completed volume, showing the Mylar-pocketed original cover boards.