Beginning in December 2022, this internship was made possible by Powering Our People, a conservation project aimed at addressing the gap in conservation skills and knowledge in industrial heritage institutions across Scotland. Funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund and Pilgrim Trust, the project’s focus has been to address the conservation needs of the 16 Go Industrial member museums, none of which currently have a conservator on staff. Over 12 months, I have travelled across Scotland, visiting each member museum to meet with collections staff and volunteers, and discuss how the project may benefit their collections.

These visits have involved project work such as condition surveys, bespoke workshops and manuals, integrated pest management (IPM) plans, and remedial treatments of both portable and in-situ objects from each site. As such, I have gained experience in a wide range of conservation practices, including project management and preventive conservation strategies, as well as numerous opportunities to improve my bench skills.

Many of the objects I have worked on from the various Go Industrial sites have been composite, including an early 20th century Louis Vuitton travel trunk from the Scottish Maritime Museum, and an Architects Drafting Table at the Summerlee Museum of Scottish Industrial Life. As a result, I have worked on a variety of different material types, training in several new techniques and learning from various specialists around the country.

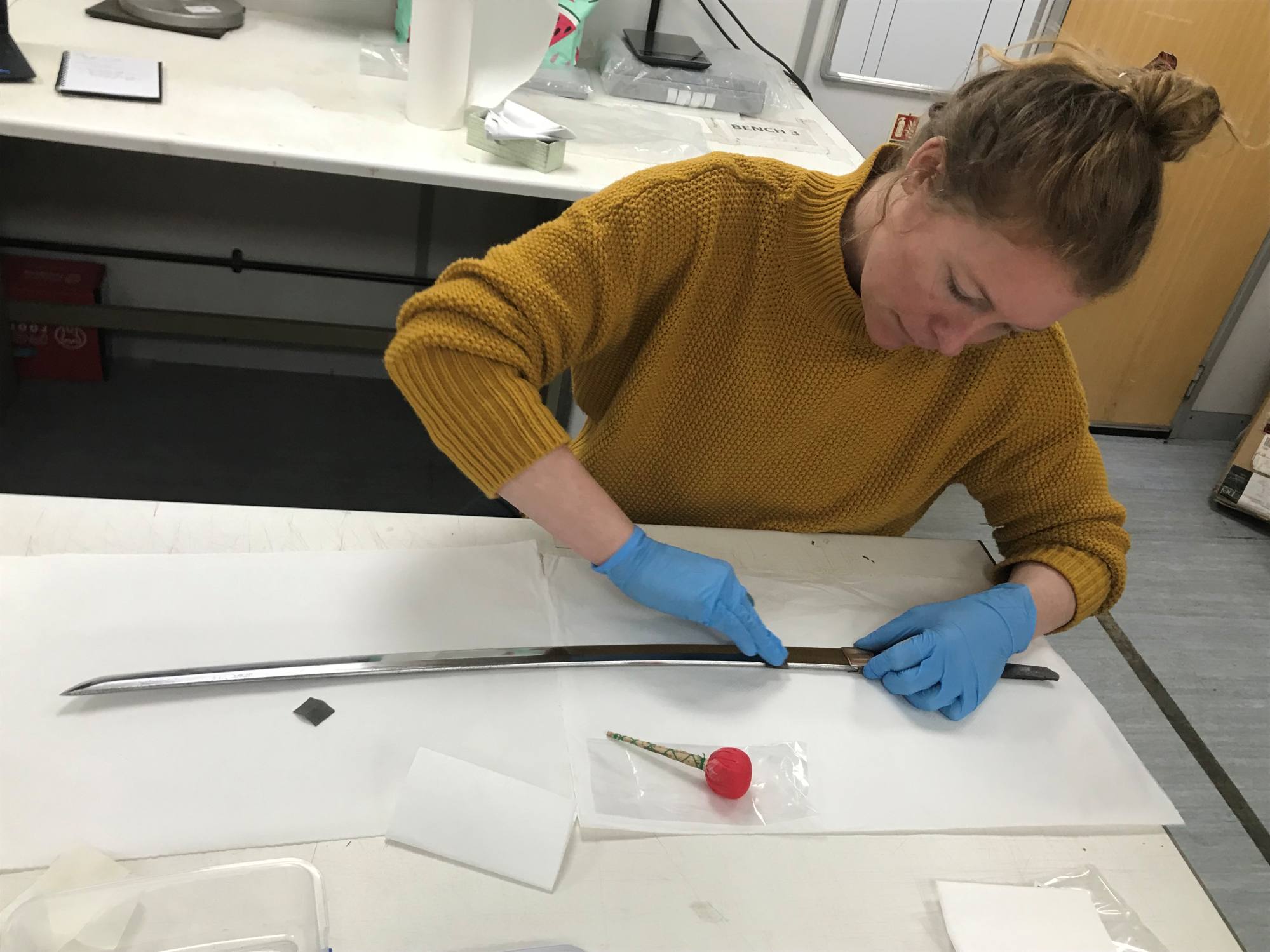

A Japanese Officer’s Katana (sword) belonging to the Devil’s Porridge Museum in Eastriggs provided an opportunity to not only work on a variety of materials, but also a chance to research Japanese traditional sword making. Confiscated in Burma during WWII, the sword has a steel blade, a leather and wooden scabbard, numerous decorative cuprous metal components, and a wooden hilt complete with shagreen covering. This remarkably intricate object was suffering from several condition issues, and I sought advice from experts on traditional methods of Japanese Sword care to address them.

This included purchasing a traditional kit to polish and oil the blade once the corrosion had been reduced. I was also able to remove the hilt of the sword to assess the tang of the blade, which was heavily corroded. Reduction of the loose, powdery corrosion allowed me to reveal the inscription, known as the Mei, while the more solid corrosion was left intact to avoid causing any alteration to the inscription or to the fit of the hilt.

As my internship come to an end, I am conscious of how much I have learnt, both in terms of conservation techniques and practices, about conservation ethics, and about Scotland’s Industrial Heritage. Working with each of the Go Industrial member museums over the past year to preserve these nationally significant—and hugely diverse—collections has been extremely rewarding, and I am grateful AOC Archaeology offered me a short contract so that I may stay on and continue to work on the project.