We speak to Icon member Fran Coles ACR who reflects on the conservation and display of the Edward Colston statue after it became the focal point of a #BLM protest

There have been several major events over the last three years that have driven Bristol Museums’ contemporary collections and allowed us to record the mood and voices of the city. One of these includes the Black Lives Matters (BLM) protests, with the toppling of the Edward Colston statue marking a significant moment in our history as a city.

About Edward Colston

Edward Colston was a wealthy Bristol merchant during the late 17th century. For many years he was celebrated as a philanthropist, with schools and public buildings founded in his name, and in 1895 a statue was raised in the city to commemorate him.

However, he made much of his wealth through the trafficking of enslaved Africans and throughout the 20th century, there had been calls for the statue to be removed. In recent decades it has been at the centre of protests and interventions, until – perhaps almost inevitably – the statue became the focal point of a BLM protest on 7 June 2020.

As protesters gathered around the base of the statue, a small group eventually climbed the stone plinth, attached ropes and pulled it to the ground.

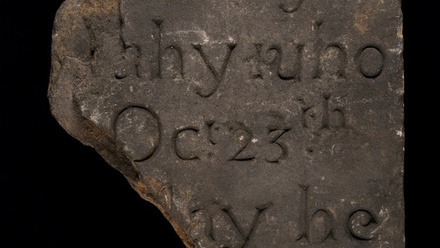

Looking at coverage from the day, we could see that it was at this point that the cane and one of the coat tails were lost. The statue was then tagged with graffiti before it was rolled almost half a mile along the road to the harbourside, where it was upturned over the railings, into the water below.

The statue

The city’s public art doesn’t normally fall within our museum remit. We will often provide advice and support to our colleagues, but as these are not accessioned museum objects, they do not form part of our collections. During the week that followed the protests, senior staff at the museum were briefed that we might need to provide support, if or when the statue was removed from the harbour. We were notified by the Mayor’s Office on Wednesday 10 June that the statue would be raised from the harbour early the following morning and that we would need to be present to see it into safe storage.

It was at this point that I became involved, as I was the conservator available at a time when it was difficult to travel and we were all balancing work with home commitments and health concerns due to Covid. Our Collections Documentation Officer and I arrived at the harbour to document the removal of the statue and to ensure all material that was raised with it was also kept.

Once the statue had been delivered to the secure store, I was able to assess it for damage and undertake the first of several stages of stabilisation. Despite only being in the water for a few days, mud had filled the insides and obscured the evidence of what had happened during its journey.

As an organisation, we have a strong focus on contemporary collecting and particularly on collecting material that focuses on the history and people of Bristol.

It almost went unsaid that our approach would be to retain and stabilise the object as found.

Working closely with our History Curators we are aware of the significance that damage, patination and use can have in shaping the story of an object. It therefore almost went unsaid that our approach would be to retain and stabilise the object as found and not to restore it to its former state.

The only deviation from this was the decision to remove the mud and residues from the harbour, as this could have put the statue at risk of long-term instability, leading to accelerated corrosion and potentially the loss of the graffiti.

The media

As conservators, we are used to being in the background, quietly working away on projects – it’s not often we are the first people the media approaches for an interview!

Being asked to pretend to conserve something when I didn’t have the appropriate tools, working with the press office to ensure any content I put out was in line with council messaging, and gaining the media’s trust so that they would ask me back to do more was all new and daunting.

However, although I was worried I would say something out of place, the opportunity to talk about conservation in this context was truly a privilege.

I realised that the public’s perception of me as a conservator was that I would want to make the statue shiny and new.

There were tens of messages asking if we would be keeping the graffiti and a lot of happy, surprised people when I said that we would, as this was now part of the statue’s story.

I also learned when to respond to critical comments and when to leave these well alone. I surprised myself when responding, finding a tone that seemed to work to defuse some of the more aggressive responses, while informing others who were genuinely interested in what I was doing.

This is just a preview of the original article which has been edited and shortened. Read the full article covering the complete conservation approach taken, the conservation of the protest placards, and what will happen to the statue next in the first issue of the Iconnect Magazine.