The Monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos, hidden away between the rural and most curiously named villages of the province of Burgos, is a 10th century Benedictine abbey and designated Spanish historical patrimony.

It is situated an hour’s drive south of the city of Burgos, home of the Cid and of many pilgrims during their pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. This beautiful abbey is mainly known for two things: its cloister and for its singing monks. The cloister is considered to be one of the master artworks of the Romanic art period in Spain. The singing monks’ music became a number one hit in the U.S. during the 1990s and sold over 6 million copies worldwide with their enchanting Gregorian singing (which, if you happen to be interested in can still be heard during mass in the monastery, or be purchased online).

There is something else that the Monastery might also be known for, although usually by a much smaller, restricted audience: inside their 1000-year-old library, Silos holds the oldest sample of Western paper in existence. This paper is found within the pages of a Mozarabic breviary manuscript. The paper dates to the 11th century and depending on different sources, the very specific the dates of 1072 or even 1036 might appear. However, I have not found arguments strong enough for either of those dates. What is definitely true is that Manuscript number 6, as it is also known in the monastery, was definitely written before 1089 – and so, its paper, must predate that year as well.

The manuscript is a Mozarabic breviary and missal, including chants and texts that were used during the daily mass services by the monks. The fact that it is based on the Mozarabic rite is particularly important, since it allows us to date the manuscript to before 1089, year in which the Mozarabic rite was suspended by the church, and replaced by the Romanic rite.

I stumbled upon the existence of this manuscript inadvertently while reading about western paper conservation on Wikipedia, and upon further research found that there are a few articles and research papers written on it. I found this to be a small amount of literature for what I had just discovered as the origin of paper in Europe and in the whole of the Western civilisation. Given that my family lives in Northern Spain and I would be visiting them for Easter, I decided to write an email to the library, asking if it was possible to view the manuscript. The library of the Monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos has an extensive range of manuscripts, and researchers are allowed to request to view them. In my email, I explained I was a paper conservation student and very keen on learning more about the arrival of paper to Europe.To my surprise, a few days later I received a reply from the Abbot of the monastery, who is in charge of the library, inviting me to go visit the library and view the manuscript.

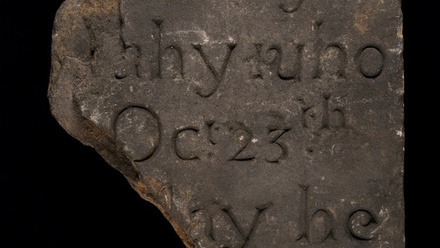

Upon my arrival, I was taken to the library where the manuscript was awaiting. From an old black and white image I had seen in a 1969 article, I expected to see a big, old, broken book. Instead, I got a small and pristine one. But if the brown leather 1970s re-binding was disappointing at all, what was inside made up for it completely. The first 38 folios are paper, while the rest of the book is made up of parchment. Both the paper and the parchment are in great condition, having been conserved in the 1970s. Previous to conservation, humidity, mould and mice had damaged some of the pages to different extents, but the infill repairs carried out seemed of good quality. Despite their age and the repaired losses, the paper and parchment folios were in a beautiful condition, the writing still completely legible.

The nature of the paper was quite thick, fluffy and of a cream to yellow colour with some darker fibres visible in some areas. Basic testing of the fibres back in the late 1960s showed themto be mostly flax, and a small amount of straw. The origin of the flax from the observed characteristics of the fibres was said to be cords or ropes. The fibres had been frayed, macerated, and beaten but not refined, giving the paper its thick and fluffy nature. On some of the pages, particularly the parchment ones, some illuminated letters can be found – although these are not overly extravagant, since the book was used by the monks and not made for a rich client. On the parchment pages, remnants of the holes used to make the lines are still visible. Small music notes can also be seen in between lines on the pages containing chants.

Although the exact origin of the paper or the manuscript cannot be traced, it is speculated that the manuscript was not created at the scriptorium in Silos, but in the more northern monastery of Santa María la Real de Nájera. The paper itself is thought to have been made in Islamic Spain. The limits of Islamic Spain were not far from this monastery, and thus the probability of the paper traveling to the scriptorium in Nájera seems quite plausible. It is unknown when the manuscript arrived at Silos, but what is known is that during the Spanish Expropriation – a period in which the Spanish government took away the church’s property and goods – the manuscript was sold or given off. This happened to all the manuscripts in the library, roughly 150 back in the 19th century. Many of these manuscripts were purchased by the British Library and the National Library of Paris as they were sold in Madrid flea markets in 1875. Most of those can still be found at said libraries, while 15 of them (including manuscript 6) slowly made their way back to Silos, where they are continuously cherished for their important ties to the monastery.

Despite the fact that much of my curiosity was satisfied after this visit, there are still certain questions that linger in my mind. Could a more modern analysis of the fibres bring about newer, more correct information? Why is there no more literature on this manuscript? Are there any surviving manuscripts using similar paper, perhaps made at the same place as this one? Maybe one day these questions will have an answer, or maybe not. Yet, I can happily go about knowing that this manuscript, as well as the whole library collection, is in good hands at the Monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos, a wonderful place full of history, Gregorian chants, and many, many books.

Seeing this manuscript was an unforgettable experience, and I am forever grateful to the Monastery of Silos and Father Lorenzo, the Abbott, for welcoming my curiosity and love for paper with open arms. They have a wonderful little treasure in their hands, and their service to researchers and interested audiences reminded me of the importance of the preservation and accessibility of these objects.

The image provided is of folios 24 (verso) and 25 (recto) of the manuscript, both in paper. These pages are some of the ones in the best condition. Music notes can be seen on folio 25, as well as some illuminated letters. The whole manuscript has been digitised at the monastery to help researchers and students, but is not available online.

This image was provided by the Monastery exclusively for this article and cannot be used or reproduced in any manner. The author politely asks everyone reading to respect this wish.

Sources:

Abadiadesilos.es. (2018). .: Historia del Monasterio de Santo Domingo de Silos:.. [online] Available at: http://www.abadiadesilos.es/historia.htm [Accessed 24 Apr. 2018].

Bibliotecadesilos.es. (2018). Información – Biblioteca de la Abadía de Santo Domingo de Silos – Biblioteca de Silos. [online] Bibliotecadesilos.es. Available at: http://www.bibliotecadesilos.es/es/portada/ [Accessed 24 Apr. 2018].

Gonzalo Gayoso Carreira, Características del papel del Breviario Mozárabe de Silos, en “Investigaciones y Técnica del Papel” 9 (1972) 1-12.

And the conversations held with the Abbot, Father Lorenzo Mate, during my visit, about the manuscript, the library and the monastery.

by Arantza Dobbels MA Conservation 2019 Graduate – Camberwell College of Arts